The “Extrovert Ideal” and the Problem with Typical Classrooms

As Susan Cain, the author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, said in a now-famous TED Talk, “Our most important institutions – our schools and our workplaces – are designed mostly for extroverts and for extroverts’ need for lots of stimulation.”

Indeed, in rejecting the lecture-based classes of the mid-20th century, schools have created classrooms that demand active participation and collaboration. Research conducted at Southeastern University in 2022, which examines the relationship between

student temperament and teacher perception, found that these types of classrooms can produce environments in which “introverted students may find themselves being asked to behave in ways inconsistent with their personality type and without adequate time for processing and reflection.”

Class design is just a symptom of a more entrenched, more insidious problem. According to Cain, “the vast majority of teachers report believing that the ideal student is an extrovert…even though introverts actually get better grades and are more knowledgeable, according to research.”

The vast majority of teachers report believing that the ideal student is an extrovert.

Susan Cain

That belief not only unfairly penalizes introverts – it also doesn’t produce the best outcomes in classrooms. Heidi Kasevich, the visionary behind the Quiet Education movement, said in a conversation with R.E.A.L.® founder Liza Garonzik that “research shows that in a team of six to eight, you have three people doing 70% of the talking. If you translate that into the way we typically assess for classroom participation, which is based on quantity rather than quality of speech, then we’re really leaving behind a third to half of our student population.”

Kasevich explains, though, that this isn’t an intentional slight: “It’s inadvertent. I don’t think there are any teachers out there who are trying to wage war on the introverts. It’s just that the ‘extrovert ideal’ became embedded in school life.”

I don’t think there are any teachers out there who are trying to wage war on the introverts. It’s just that the ‘extrovert ideal’ became embedded in school life.

Heidi Kasevich

The Extrovert Ideal and In-Class Belonging

Teaching in ways that align with such an “extrovert ideal” does not engender a sense of belonging for introverts, who may feel anxious and drained when they come to class – particularly to classes where they’re expected to participate vocally. They may not

feel that their way of thinking and learning belongs in the classroom. As a result, they may not find the opportunity to develop and share their thoughts and opinions, and extroverted students may not realize the commensurate opportunity to benefit from

those perspectives.

A 2020 study of students across Finland found a correlation between introverts with high social engagement and higher self-esteem. “Our results implied that introverts should be given extra support when they encounter group work in school,” concluded the researchers.

“Introverts are deep, reflective thinkers,” says Cain. “They’re careful thinkers. They come up with insights that others don’t just by sitting and thinking things through rather than verbalizing ideas right away…In the company of introverts, extroverts feel permission to be themselves and to talk more deeply, while introverts find that extroverts bring them into a more carefree and lighthearted zone.”

Kasevich concurs with this thinking. “The introvert is taking the time to really think and then, later on, if they believe the space is safe enough, the introvert will be able to vocalize their thoughts,” she says.

A study exploring the differences in argumentation style between introverted and extroverted students found “striking” differences between the two personality types: introverted students typically preferred a “co-constructive” argumentation style, whereas conflictual argumentation was more strongly associated with extroverts. “It is important to note that unlike the extroverts, the relatively more introverted students did not rigidly adhere to different sides of the argument and attempt to win others over to their side,” explains E. Michael Nussbaum, the author of the study. “Rather, the introverts worked together to build and critique solutions” (Nussbaum, 2002).”

Learning from Each Other

In class and in life, extroverts will need the ability to work collaboratively with others toward a solution, as well as the skill of debating and defending their own ideas. Truly, both types of students have important lessons to learn from the other’s learning styles.

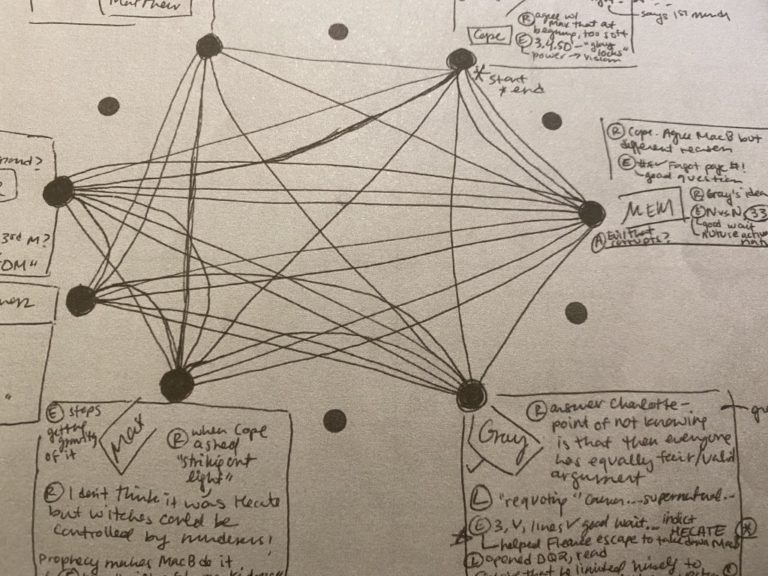

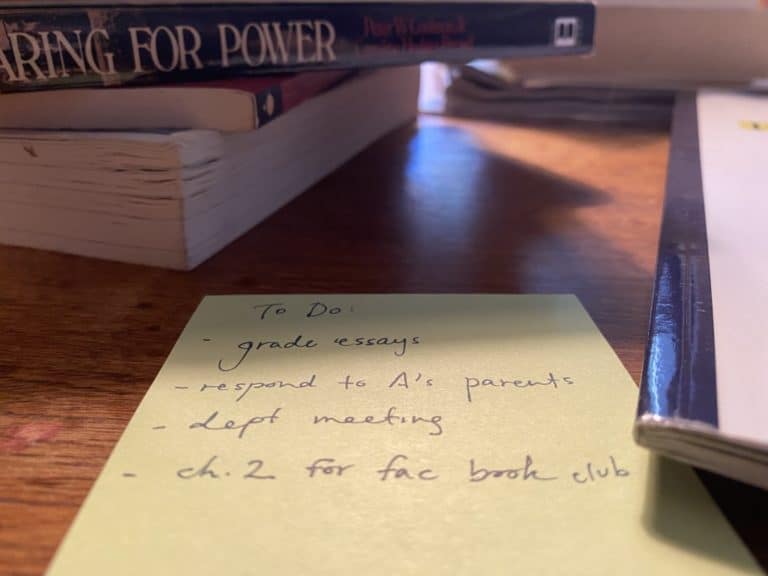

Developing the skill of co-constructive argumentation is important for extroverts as well as introverts. Today’s typical classroom, though, doesn’t create the ideal space for the sustained, multifaceted growth of both introverts and extroverts. As a result, teachers

are constantly writing comments like: “I wish we heard your voice more often!” to their introverted students and “While I love hearing your ideas, I hope that in the next discussion you can leave space for others” to their extroverted ones. These two types of

comments don’t acknowledge specific tactical moves students can make to engage with their classmates in discussion – which would be part of a carefully-designed discussion learning environment.

Today’s typical classroom doesn’t create the ideal space for the sustained, multifaceted growth of both introverts and extroverts.

So the question for educators is: how can we design class discussion to engage, challenge, and celebrate extroverts and introverts alike? We need to create classrooms that explicitly teach today’s students to speak — and to listen.

Interested in learning more of our thoughts about how and why we need to create these types of classrooms in order to engage and empower all types of learners? Read our whitepaper: Designing Discussions Where Extroverts Practice Listening and Introverts Practice Talking.