Office Hours with Mary Finn

The Office Hours series recruits experts from within the field of education and beyond to share their specific knowledge and perspective on a topic or a series of topics. This week, we spoke with Mary Finn, the founder of Premise. A note for our readers: any reader can use the code “Realdiscussion” for one free Premise course in 2022!

Let’s talk, first, a little bit about your background and who you are. How did your story lead or contribute to your decision to found Premise?

I was a teacher and school administrator for about twenty years. I stopped two years ago, when I transitioned to work for an equity-centered tech company that partnered with school districts. I am and always have been very interested in discussion-based learning environments and circles, and those interests grew stronger through curriculum and teacher training programs like the Touchstones program. I was partnered on an NEH grant with Touchstones when I taught in Washington, D.C. Public Schools, and they introduced me to seminar styles teaching and learning strategies.

Another influence that led to my interest in discussion-based learning was my experience in the graduate program at St. John’s College, which uses an all-seminar program in both undergraduate and graduate programs. St. John’s lets teachers complete degrees across summer semesters, and the degree took about eight years to finish. Through my student experience at St. John’s and trial and error in the classroom as a teacher, I learned how to plan and run discussions in classrooms. I came to understand that seminar-based learning is most powerful when it is properly structured and scaffolded. That approach was true to my origins as a teacher: my teacher training was through Brown University in the late 1990s, and in my program there was a strong emphasis placed on constructivist education and the use of driving essential questions in the classroom.

As a teacher, then, I’m rooted in the practice of student discussions. Premise was born of that training and my strong desire to help people, especially adults who are out of college and feel their lives are too busy for connection and learning, to find time to make meaning together.

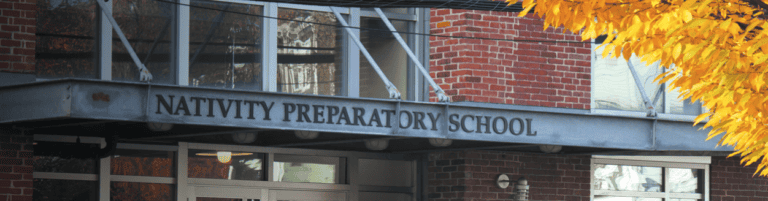

In 2013, when I left my last school job at Lick-Wilmerding School in San Francisco, I had taught public, charter, and private schools. I had an itch I wanted to scratch to continue to have meaningful, purposeful, joyful conversations with adults. I tried to join book groups and take long form courses, but neither worked well for me. I found that the book club scenario was less facilitated than I was hoping for; I didn’t know what to expect when I got there, because sometimes the group involved more wine drinking than book talking. The long form classes were arduous as a full time worker, both in the tuition and the length of time they required.

I started a program similar to Premise, called Polis, in San Francisco in 2013. The idea was born out of an NEH fellowship on Hannah Arendt, which took place at Bard. Polis was my culminating project, an attempt to take Arendt’s ideas of making a common world by grappling together and make an accessible and joyful space for adults to do that grappling together. I rented space at the Women’s Building in San Francisco and held classes a couple of times a month with fifteen to twenty people. That experience lasted about three years, and I learned a ton from it. I was a facilitator, and I also had a group of people who ran classes. In all of this work, I want to make sure that the learning is joyful. The most popular series was called “Drinkers and Great Thinkers,” and each class paired a beer with a thinker.

I have a lot of ambition around this kind of work, and I’m mainly learning about starting a business by doing. I’m learning from building Premise. I moved up to Portland, and Polis ended. Then, the pandemic hit. I had been teaching classes through Portland Literary Arts Foundation, and they moved online during the pandemic. I’d designed courses at Portland Literary Arts including a five-week session on Arendt. I realized through that discussion that my mental barriers about doing it online weren’t necessary, that there were some real opportunities that come with teaching online. I taught three classes with that organization during the pandemic. The itch (to educate adults) was still there, and something wasn’t quite right in the model we were using. What I want to be part of and am creating with Premise is a program that has a really strong pedagogical thread that runs through all of the classes, so it doesn’t feel like the success of the experience depends on the teacher. I want to have a range in texts and instructors, but I also want commonality through a strongly defined pedagogical approach. Students should be able to anticipate no structure no matter what course they’re coming into.

I started to build Premise in February last year. The work involved finding instructors aligned with the pedagogical model who could apply it to content. Diversity in all kinds of ways was important to me. A lot of adult learning programs out there lean older and mostly draw in retirement age audiences. Or, they lean toward a canonical, “great books” style of learning. At St. John’s, I appreciated that “great books” style, but it’s not for everybody. I wanted a less canonical, more age-diverse community, and I also wanted more diversity in instructor age and background.

I also want Premise to be inquiry-driven, rather than leading with author or text. Each class is designed around an enduring or “beautiful question.” Instructors propose an enduring question and the text that they want to use with the class to probe that question. Then they design the class. I have a pretty open idea about what kinds of texts get at these enduring questions, but it’s a wide range. I want classes to have modern applicability, which looks like pairing Lysistrata with Spike Lee’s Chi-raq. I think that can lead to more intergenerational participation.

Ultimately, that’s where Premise came from: I’ve been looking for something like this and haven’t been able to find it. I have a feeling that people are going to increasingly need an explicit way to connect around the mind. The president of Barnard said, a while back, that “you want your mind to be an interesting place to live for the rest of your life.” That happens by trying on ideas with other people. I also have a loftier goal, which is that when people practice this interaction with a range of people they might not normally meet, the world becomes a better place.

Premise focuses on the idea of a “beautiful question.” To me, the idea of a “beautiful question” reads as almost spiritual, or driven toward the pursuit of beauty, intangibles. Why do beautiful questions matter to you, and how do they drive instruction?

I think that one way to think about beautiful questions is that they offer a philosophical way to think about how we’re living, the choices that we’re making, how we’re interacting with other people. Most of the way that I got to understand my own thinking was in formal institutions, mostly schools, as a student or teacher. I explored my own thinking as a teacher through questions like these, through what teachers call essential questions. I’ve found that in a more nonacademic setting — with friends, on Facebook, in day to day life — I don’t have an opportunity to be external with a philosophical way of living without a very formal environment. This is a selfish reason to start Premise, but I have a strong desire to talk about and grapple with these big life questions in the company of others. I’m not in a PhD program or part of a religious community, so I don’t have another natural way to talk with others about how we’re living.

The most recent class “How does illness and pain define the human experience?” brought together a group made up of fourteen people from across the country. We read Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor and Zadie Smith Intimations. The conversation, it’s odd to say, was joyful; people who’d never met were sharing their own experiences with illness and death, especially in Covid, and connecting it through text. The text provides a thing in common, which helps to make the conversation much more egalitarian. I want the discussion to give space to connect life to text. That said, being a good facilitator often means managing that connection, so it doesn’t veer so far to the personal that we lose sight of the common, central text. My goal isn’t to have most participants in one time classes, but to provide multi-week classes through which people get to know each other over time. So far, one-time classes are what have filled, but I want them to feed into the multi-meeting classes. When it comes to me, I have this strong desire to talk to people in a safe and comfortable way to have uncomfortable experiences together.

What problems does Premise address?

I’m really interested in the “epidemic of loneliness.” I’m interested in the shame that people feel when they don’t have connection to others and what they do to cope, even to name. Premise isn’t the solution to loneliness, but I do think that when we all experience disconnection in many ways and for many reasons, and there’s not a great accessible place for explicit connection. There’s a lot in the news lately about male friendships in the US, about how challenging it is for men to make new friends. I think that it’s unlikely that someone’s going to join the community if it’s explicitly named to make friends. But if that’s a side effect, that’s going to be an enormous benefit for many.

Another challenge, or problem, in the world now is a lack of quality thinking — not just critical, thinking, but also nuanced thinking. Many of us lean into black and white decision making and thinking and are unwilling or unable to live in the gray. Some of these classes are designed to have participants occupy the gray space, at least for an hour and a half. I’m in a social media world, and I find myself feeling really polarized, but unintentionally. This class experience can be an antidote to that feeling.

It seems like Premise deemphasizes the idea of an end product or a “finish.” This idea is more accessible to adults, it seems to me (as a high school teacher), than it is to kids. How can schools center the process of discovery over the product? How can we enlist more people, of all ages, in building that mindset?

One of the hard things is that I feel some pressure to have Premise become something I don’t want. I want Premise classes to be for the sake of themselves, not ending in badges or certificates. I want it to be an ongoing experience from which people derive meaning for meaning’s sake. It’s difficult to have education for its own sake, especially because there is facilitation and structure. Maybe at the high school level it’s more micro-experiences where we can make that happen. It’s unrealistic to think that kids won’t jump through hoops set before them or fixate on those hoops. Within a class, when teachers can try to name the moments that are for the sake of themselves as they’re happening — try to be a bit meta, talking about how it feels — that can help students to become more aware of that work. Name the learning. Name what can happen when kids construct meaning together, not in an individualized or competitive construction. It’s not easy, especially in a college prep context, but I do think it’s possible. I want Premise to bring the feeling you get when you walk into a dorm room at a liberal arts college at midnight and come upon roommates in a spontaneous deep, philosophical conversation. That feeling of witnessing a conversation that you really want to hear and really want to join — that’s what I want to recreate.

Education can be really performative, even when it’s called “Authentic.” Upper middle-class college bound kids, especially, tend to know how to perform authenticity. One thing I like about Premise is that there’s no need to perform.

I often think about Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings, where she talks about the imperative to perform dialogues of experience based on the situation. When we talk about authenticity, it can translate into expectation, pressure, and even danger.

Priya Parker’s Art of Gathering has been very important as I’ve started Premise. The art of gathering with purpose has a lot of applicability to a high school classroom but also in adult learning contexts. Parker writes that we have to be explicit about why we’re together and not assume that there’s a common understanding of purpose. Then, you set guidelines and boundaries. With a book club, there are no limitations. I once watched a ceramics class with limited resources, and that course produced more creativity than a class with unlimited resources did, because with unlimited resources, it was too easy to just scrap an idea. Limitations produce better thinking.

How do leaders at Premise teach? What does Premise take from education, and how could teaching from Premise carry over into formal classrooms?

I’ve done a lot of planning professional development for adults in my professional life. In doing that, I had to think about what kind of pedagogy translates to an adult world but doesn’t infantilize adults. There are strong pillars from high school teaching that live in Premise. Making guidelines that are known and recognized is huge. I send all students the guidelines for convo in advance of class and ask to read, then review and give examples when they’re in the room, and I do that for every class. Maybe that won’t be as necessary over time, but it starts us from a common place of what we’re here to learn and how we’re here to learn. I think that not doing as much hand holding and assuming an adult perspective is also part of how we teach in the class. Something I’ve seen in other programs is the opposite: they assume that because we’re all adults, we’ll be offended by structure, feel constrained by it. I think that structure is freeing; structure allows for voices that may not normally feel they have a place. St John’s overdoes it with structure, but it’s helpful in the end.

What’s a goal or a prediction that you have about or for the future of education?

I kind of think about it like Whole Foods. When Whole Foods started in the 70s, most people thought that it was niche, artistinal, boutique. Then the pendulum of understanding processed food started to swing, and now that way of thinking about food is more integrated into mainstream life. I’m not, we’re not, creating from scratch a new way of learning; rather, we’re borrowing from a long history. The pendulum has been so far to the “drill and kill”and knowledge acquisition side, and I still feel like this kind of discussion-based learning, in most education settings, is seen as a “nice to have but not essential” feature. My prediction is that kids and adults will want more and more of this over time, either because they’ve had a sample and realize it’s different, or because they understand the damage that’s done by the more individualized, knowledge-acquisition driven learning. So my prediction is that people are going to start to push back on how we’re doing school.

Thank you for your time, Mary!

Premise was featured in this EdSurge article last Friday. Click through to read more about Mary’s work and the ways in which it fits into Humanities education beyond the classroom!