Want to Teach Civil Discourse? Break it Down into Civility, Discourse, and Civics

As we head into 2024, “Civil Discourse” is a buzzword – and for good reason. The next Presidential election cycle looms large. Many campuses are still recovering from the hydra-headed ways politics ravaged their communities in 2020.

The most strategic school leaders I know are taking a proactive approach, asking: How can we use ’23-24 to build the skills and culture for civil discourse our community will need next year?

As a former teacher and administrator who now works with schools to design philosophies and programs for discussion skills, I often see schools begin with this worthy question – then answer it by designing programs explicitly focused on politics. This might sound like:

- Let’s run fora where we stage thoughtful, rigorous debates among experts with diverse viewpoints. When we debrief as a community, we’ll ideally arrive at the conclusion that complex issues often have multiple, valid, paths forward!

- Let’s make sure our Young Democrats and Young Republicans clubs have identical budgets, airtime at school assemblies, and officer structures!

- Let’s create a program where we train a group of upperclassmen to be Civil Discourse fellows who can mediate among peers!

- Let’s stage debates among middle schoolers, where kids practice arguing for sides they don’t believe in to cultivate empathy!

When done well, initiatives like these can be extraordinary learning experiences. Too often, though, they are an add-on (and sometimes even opt-in) for students. They exist outside the core academic experience. They are facilitated by an octopi task force under time constraints that don’t allow for practice, nuanced reflection, and culture-building.

Here’s what I propose: do those things, sure. But also, zoom out. Get strategic about how to embed civil discourse skill-building within your core program for students and faculty alike. Spoiler alert: this doesn’t mean talking about politics all the time – and these are essential human skills that will serve your students and community well far beyond the 2024 Presidential election.

Get strategic about how to embed civil discourse skill-building within your core program for students and faculty alike.

For students: begin by acknowledging the reality that kids today struggle to talk, never mind actively listen, to each other – even when the conversation is not political in nature! Your students need training in (and low-stakes opportunities to practice) the mechanics of conversation: how to attend to each other, how to self-express and self-regulate in real time, and how to make space for other voices.

For faculty: start with the assumption that they are all over the map. Some may be too scared to facilitate any kind of discussion among students while others might struggle to imagine a world where their political identity is separate from their purpose as an educator. Most crave a clear, school-wide philosophy and set of admin-approved tools for teaching and facilitating discussions – and a school-wide growth mindset when it comes to embedding these skills in their professional practice.

Put differently: to build a campus culture of civil discourse, you must first equip teachers to teach the foundational communication and relational skills students need to engage with each other.

Today’s students are growing up in a world where manners are at an all-time low, live conversation is scary, and algorithms can short-circuit civic literacy. Teachers deserve clear direction, concrete tools, and grace as they build their facilitative capacity amidst these dynamics. We can’t afford not to start with the basics.

Sounds nice, but what does this look like? The path won’t be the same for every school, but let’s consider options for each step along the way: Civility, Discourse, and Civics.

Teaching Civility

The first step in teaching civility is acknowledging that it is (sadly) counter-cultural. You might ask your faculty to begin by considering their own observations about public behavior today or zoom out further with David Brooks’ recent article: How America has become mean. Brooks makes the case that the seeds of our incivility date back to the 1950s – i.e., this is not just a COVID thing! His perspective is that through a combination of economic, technological, social, spiritual, and academic forces, we find ourselves in a world where compromise or any type of decision that places the good of a group ahead of your own desires – the basis of civility – has become a sign of individual weakness, not collective strength. Another specifically education-focused resource is Grant Lichtman’s new taxonomy for 21st century learning. For Lichtman, civility is the foundational skill upon which deep learning and belonging rest – akin to “remembering” in Bloom’s taxonomy.

Once the “why?” is established, it’s time to define civility for your campus. For example: “at our school, civility means paying attention to each other and consistently making decisions that benefit community instead of self.” Don’t overthink this step!

Then, call faculty to be empathetic to and curious about students’ apparent incivility: why might this kind of personal trade-off be counterintuitive for today’s kids? Well: on-screen, today’s teens don’t have to wait for others to speak before expressing their own opinions; they can impulsively swipe or disengage with no consequences. Algorithms have conditioned kids to expect the world to anticipate their needs. So then, it makes sense that kids operate in real life with a certain self-centeredness and unrealistic expectation of personalization: little things – like a surprising comment or logistical hiccup – can then feel like injustice rather than a simple part of life! This dysphoria – combined with the easily-hijacked rhetoric around the righteousness of self-expression and the stunning fact that one in four Gen-Z students says their career aspiration is to be an influencers – has produced a generation that literally struggles to navigate civilization as we know it.

Today’s students need to be taught that being part of a community requires a million little personal sacrifices – complying with a dress code, following rules about assembly behavior, or participating in after-school activities no matter how badly you-just-want-to-play-Fortnite. In the aggregate, those sacrifices are not oppressive; they are the price you pay for the support you get from the community in which you participate.

In the aggregate, small personal sacrifices are not oppressive; they are the price you pay for the support you get from the community in which you participate.

Civility must be modeled and celebrated as much as it is taught – and all faculty and staff can help with this culture-building. The key is to make civility visible and explicit! Easy wins here can include:

- Expect students to hold the door (every time you do that, you’re saying to the person behind you, ‘I see you!’ and ‘I’m willing to get to my destination three seconds later to do this thing for you!’).

- Ask students to write monthly thank you notes (with specific examples that say to the recipient “I heard what you said or saw what you did. Here’s the impact on me, and I am grateful”).

- Normalize the expectation that students (and adults) say Hi and make eye contact on the path or in the hall between classes.

- Establish clear rules for representing the school off-campus at sports games and field trips with policies like dress codes; norms like thanking bus drivers, refs, and docents; and commitments to ask questions, stay off screens, and leave every table, locker room, and field bench clean of trash.

The best part? These micro-sacrifices will add up to a macro-impact – not to the self-repression that Gen-Z kids fear it will. In fact, civility norms will become the very foundation of belonging – which is, of course, the prerequisite for any real discussion across difference.

Civility norms will become the very foundation of belonging – which is, of course, the prerequisite for any real discussion across difference.

UP NEXT: Teaching Discourse

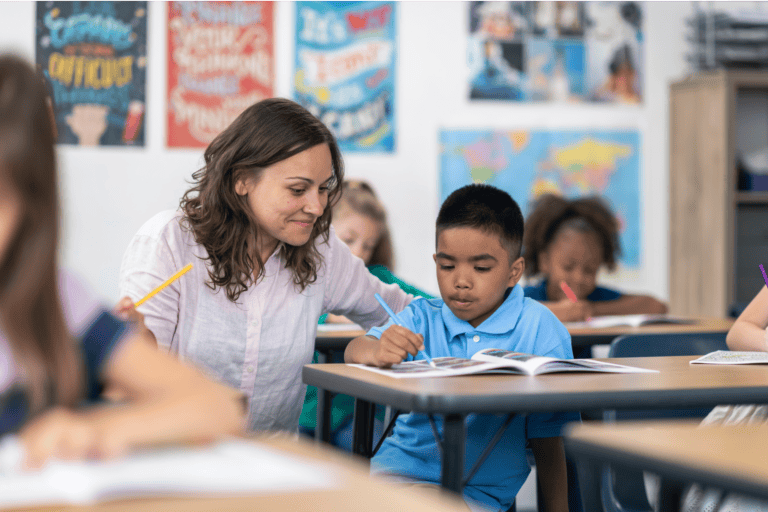

Once you’ve cultivated a culture of civility that values paying attention to each other, it’s time to teach the mechanics of conversation.

Today’s students need to be explicitly taught how to engage verbally with each other – a need researchers document as a natural opportunity cost of time spent on screen. Today’s teachers need clear guidance on what that means, who is responsible for teaching conversation skills, and how to do it.

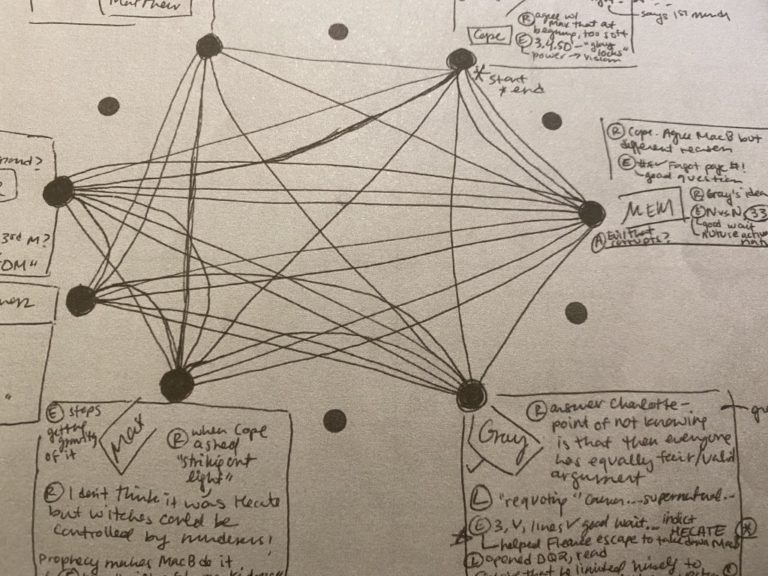

Effective discourse programs should require all students to answer questions like: How do great discussions work? What skills do they require? Why do discussion skills even matter? How do I get good at them? How do I analyze the dynamics of a discussion the same way I might analyze a sports game or artistic performance?

These are questions kids can’t answer by just “having discussions” in their Humanities classrooms. Even the most artfully-orchestrated upper-level Harkness seminar will not leave students with an understanding of why these skills matter in the world. Content-focused fishbowls in seventh grade History or debate team practices are more likely to build performance skills than any kind of authentic, transferrable capacity for discourse.

Schools need a shared language for what discussion skills look like at each grade or division level and a distributed strategy for teaching, assessing, and celebrating them. It likely makes sense to draft Humanities faculty members as experts who are in charge of the heavy lifting. These leaders introduce the taxonomy and give students discussion drills and feedback, while other faculty help students practice these skills in places like advisory, science lab conversations, or small group work time – and have higher-level conversations about why they matter.

Schools need a shared language for what discussion skills look like at each grade or division level and a distributed strategy for teaching, assessing, and celebrating them.

It’s worth noting that the idea of a shared language around an academic practice can cause independent school faculty to bristle. But, bristle they may! The stakes are too high and the timeline is too short for each teacher to invent a unique taxonomy (this might ignite faculty creativity but it inherently limits students’ ability to transfer those skills across classes and social contexts). In my experience – and I have worked with over forty independent schools on designing and implementing discussion skills strategies – teachers get on board when they, too, understand the “why” and see their work as connected to the extraordinary, and existential, challenges our society faces right now. Plus, as the best teachers quickly see: there is infinite creativity in how to teach and assess discussion skills in each class.

Teachers get on board when they, too, understand the “why” and see their work as connected to the extraordinary, and existential, challenges our society faces right now.

Lastly: academic leaders must proactively communicate this strategy for teaching and assessing discourse skills to stakeholders beyond students. This is a perfect moment for authentic collaboration between academic leaders and their partners in advancement, parent engagement, and admissions. Nailing your messaging –and emphasizing the mission to teach students how to communicate rather than what to think, with specific examples of what that looks like at each stage in a student’s journey – will build community-wide trust. And trust – alongside communication skills – is ballast for Fall 2024.

Last but not least: Teaching Civics

I would be remiss to write an article about Civil Discourse that focuses only on civility and discourse without a call to arms for Civics education too. Once you’ve established a culture of civility and capacity for discourse, you can leverage Civics to offer the background content knowledge students need to actually engage in meaningful conversations about the big, thorny questions at the heart of Civil Discourse: i.e., what is best for society and why?

Certainly any Civics curriculum will cover the mechanics of US democracy – think: checks and balances, bi-cameral legislature, campaign regulations, etc. – but I highly recommend that schools opt for civics curricula that include information about technology and society today, too. Children need to learn – and adults need to be reminded – that algorithms are influencing democratic life in infinite, and often invisible, ways.

Children need to learn – and adults need to be reminded – that algorithms are influencing democratic life in infinite, and often invisible, ways.

This reality is here to stay. I love Common Sense Media’s approach to the role of algorithms in modern democracy. The Civics Network, Close Up, and Symphony by High Resolves all offer other excellent civics content. Citizen University has great extracurricular content and engagement opportunities, while the brand-new Democratic Knowledge Project out of HarvardGSE is a rich, targeted experience for eighth graders.

School Leaders should consider appointing a small (!) committee of faculty members to develop Civics standards for each grade level. Unlike the light-lift work surrounding instruction of civility and discourse, devising a shared language and assessment for Civics will require more time than all folks have to give. Again: proactively share the Civics Standards with stakeholders to celebrate and ensure bipartisanship. It might be interesting to invite parents into the Civics conversation in some way, by offering prompts for the dinner table, etc.

Here’s to the Building Blocks: Civility, Discourse, and Civics!

For any campus that wants Civil Discourse in 2024, spend this year tackling the building blocks: civility, discourse, and civics. Make it a campus-wide effort, a call-to-action for faculty and students alike, with proactive messaging to stakeholders like parents, prospective parents, alumni, and donors along the way. This is the path to trust – and trust, along with communication skills, will be an anchor to windward as schools prepare for the weather of next year’s election season.