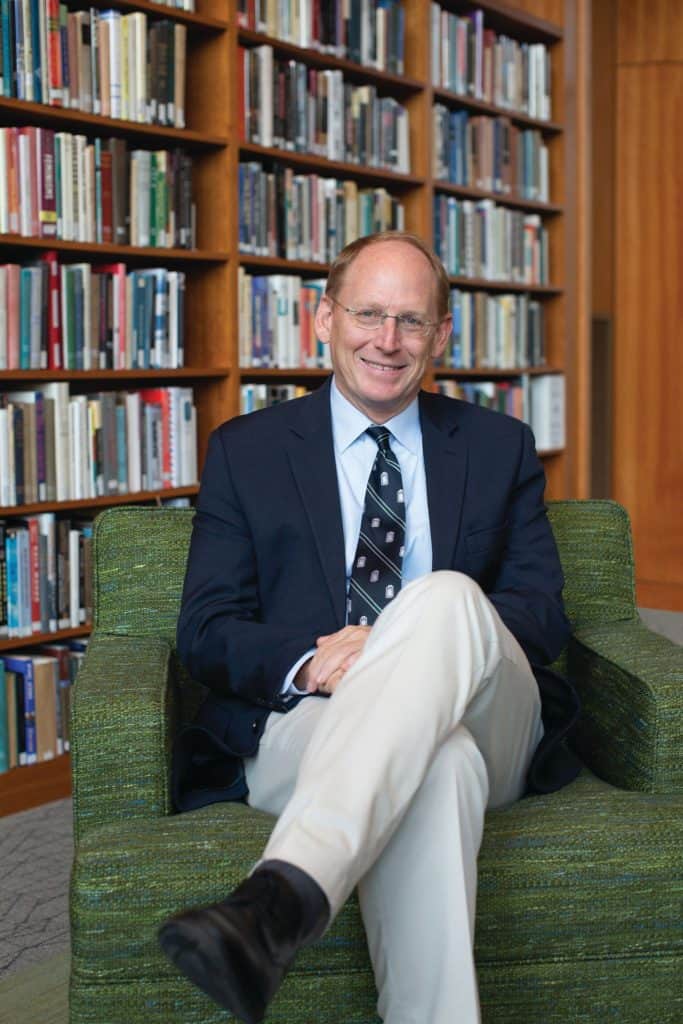

Thriving in a World of Pluralistic Contention: A Conversation with Dr. John Austin

Dr. John Austin is the Head of School at Deerfield Academy and the lead author of “Thriving in a World of Pluralistic Contention: A Framework for Schools.” The Framework was produced by a Task Force of Heads of School in partnership with the E.E. Ford Foundation.

What follows is a conversation between John and R.E.A.L. ® founder Liza Garonzik. This conversation has been lightly edited for clarity.

Liza: John, thank you so much for joining us today. We’re grateful and excited to have you. We’ll dive into the Framework shortly, but I wanted to start with you! What is it in your personal story that led you to tackle this topic and help define what “thriving in a world of pluralistic contention” means for schools and classrooms? How have you experienced these values in your own education and adult life as a faculty member, school leader, parent, citizen?

John: The Framework reflects my experience as a teacher and a school leader, and as somebody who’s spent a significant amount of time outside of the country. As a teacher, I’ve always had an interest in bringing to the classroom what Richard Light in his book Making the Most of College calls “structured disagreement.” That’s one of the things students he interviewed identified as being a very, very effective way of creating space for conversation and engaging with complicated and potentially controversial questions. This work has really emerged from a lot of reading and from my own experience as a teacher.

It also reflects my experience living outside the US – I spent nine years in Jordan, where I served as Head of School at a coeducational international boarding school founded by King Abdullah of Jordan, King’s Academy. It was an eye-opening experience for me. I got to see schools across the world, and I learned so much while I was there.

I was also out of the country during a period when the tenor of the country really shifted in a lot of ways – I moved back to the US in 2019, just in time for COVID and the extraordinary summer of 2020. I came back to an independent school landscape that was fundamentally different than the one I had left. I felt like there was an opportunity to define some principles that could help schools navigate the sheer amount of conflict that had become the norm.

Liza: Wow – what an extraordinary moment to transition back into the US. Now let’s turn our attention to the Framework itself. What’s its purpose? How do you hope schools use it, or perhaps, don’t use it?

John: The purpose of the framework is to provide people with principles: to ground school leaders and teachers and help them navigate their way through conflict. It’s also a way to help leverage, in some ways, the polarization we see on campuses.

Polarization is not inherently a bad thing – it simply depends on how you engage with it and the kinds of practices you adopt in order to create an environment on campus where really complicated questions can be pursued in a thoughtful, curious way.

Polarization is not inherently a bad thing – it simply depends on how you engage with it and the kinds of practices you adopt in order to create an environment on campus where really complicated questions can be pursued in a thoughtful, curious way.

Dr. John Austin

Certainly, I hope the Framework is helpful to schools as they think about political events that are on the horizon, including but not limited to the 2024 Presidential Election. I’ve heard from Heads who have said that simply to have permission not to speak on every global issue or conflict or tragedy that happens is liberating in a certain kind of way.

If schools want to adopt it, that’s great. If they want to adopt part of it, that’s great too. If they want to reject it out of hand, that’s fine as well. It’s really intended to be a provocation: a way to encourage people to ask the right questions. That’s the strength of the American independent school space: it’s a big tent. It’s pluralistic. It makes space for a lot of different kinds of schools, so I hope and expect that schools will all engage differently with this framework!

Liza: I appreciate this framing as a provocation and your openness to this Framework being used differently by different people and different schools. This is a perspective that invites people in, whether that’s an individual teacher in her classroom who’s struggling with a group of 16-year-olds who don’t know how to communicate with each other, period – never mind about a really complex, high-stakes idea, or a group of senior leaders operating at a systems level, managing boards or communicating to stakeholders. This is an invitation that I hope schools take seriously at all different levels.

John: For me, the great question is: how do you create a learning environment that’s both respectful of pluralistic difference and that seeks to leverage it as an educational benefit for every student at the school? Pluralistic contention is inescapable. In some ways, it’s the reality of our schools, and it’s certainly the reality of the world our kids are going to enter and graduate into when they go to college and work and beyond. They need to be skilled at engaging with different things – even things that they profoundly disagree with.

Pluralistic contention is inescapable. In some ways, it’s the reality of our schools, and it’s certainly the reality of the world our kids are going to enter and graduate into when they go to college and work and beyond. They need to be skilled at engaging with different things – even things that they profoundly disagree with.

Dr. John Austin

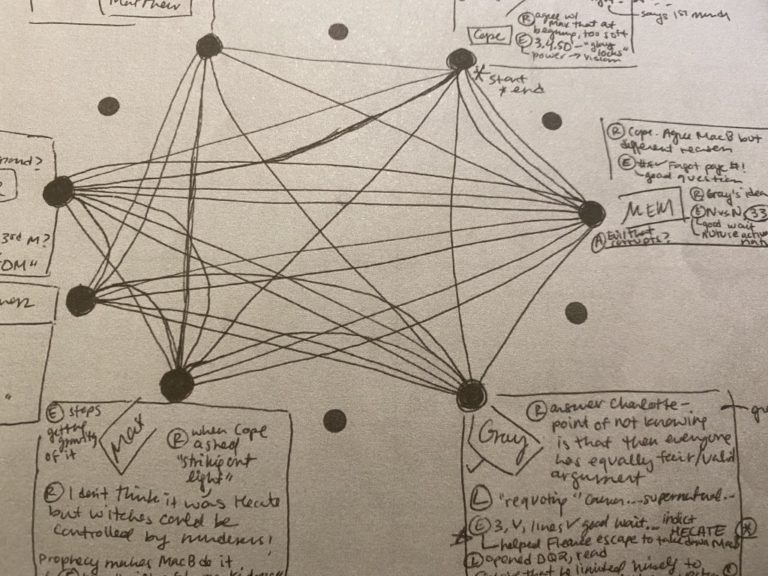

Liza: Absolutely. Hearing you define pluralistic contention in this way makes me think of one of our favorite moves to teach teachers and students – a method we call In-REAL-Time Notes. We ask students to take note-taking breaks three times throughout a discussion. Each time, students write down the name of a peer, summarize the point made, and explain how it changed or challenged their thinking. At the end of the discussion, students read these notes to each other. This increases active listening skills, sure, but it also reminds students that the purpose – and the joy and the beauty – of discussion is to have your thinking changed and challenged by others! I hadn’t thought of it this way before, but In-REAL-Time notes require pluralism and normalize contention.

The Framework has three core principles: expressive freedom, disciplined nonpartisanship, and intellectual diversity. Let’s walk through each, defining the pillar itself and then considering what it looks / sounds like when a School lives into it.

Let’s start with expressive freedom.

John: Expressive freedom is an essential precondition for robust inquiry – kids need to be empowered to speak and to listen deeply and thoughtfully. Kids have to be willing to listen to things they really find troubling.

Expressive freedom is an essential precondition for robust inquiry – kids need to be empowered to speak and to listen deeply and thoughtfully. Kids have to be willing to listen to things they really find troubling.

Dr. John Austin

The whole point of that section of the framework is trying to answer the question: what does a vibrant, dynamic, expressive environment look like on your ideal campus? We particularly talk about that critical period when students are moving from childhood into young adulthood. What are the habits and attributes they need in order to create a culture on campus where everyone can learn and ask questions and think deeply about complicated questions?

I consider each of those pieces — conscientiousness, toleration, and courage — to be kind of indivisible. You need all three. And it’s not about creating some kind of rule-bound or rule-based regime. That can be where things get tricky.

I tend to approach the question of expressive freedom from an educational perspective. What kind of ethos do we want on campus? When complex issues land on your campus, will the kids be able to manage themselves? That’s why those three pieces are so important. If we can help kids learn to listen deeply and carefully and generously and empathetically, if we can help them learn how to how to ask and frame really challenging questions in an uninhibited way, and if we can also, at the same time, help them learn how to use language well, conscientiously, with an appreciation for how our words land with others…if we can do those three things, I think we’re going to graduate young people who are well-equipped for pluralistic contention.

My problem with the phrase “free expression” — and “free speech” is even worse — is that the idea often gets kind of sloganized. That’s not really what we’re after. I’m not interested in encouraging kids to say the first thing that comes into their heads. We want them to express themselves, but we also want them to hone their language and be thoughtful about it as well.

Expressive freedom has implications for your handbook, for your pedagogy, for orientation, for the kinds of student-centered groups and organizations you create beyond the classroom. There are lots of opportunities there once you think about it.

Liza: I appreciate the idea that expressive freedom isn’t just about speaking – it’s also about listening, and everyone has a responsibility to be on the receiving end of ideas in order for expressive freedom to flourish. What’s an example of expressive freedom if you’re talking about a board meeting or a faculty meeting?

John: I think the best boards have to create that kind of culture in the boardroom. Boards have to be able to talk about really complicated things. You’re going to come to a better place and potentially a better position or solution if you have a diverse board that’s willing to talk these through and consider them really, really carefully.

Liza: You might even say that’s the point, right?

John: Yes. If you don’t have sufficient diversity, or willingness of board members to ask questions or express skepticism, then you’re probably not going to come to a good and thoughtful decision. And the issues that boards are dealing with are really, really complicated right now.

Liza: Absolutely. Ok, the second pillar: Disciplined Nonpartisanship. Can you walk us through that?

John: There are two pieces to that. First, there’s the role of the school: the school leadership, and particularly the Head of School. I’m of the view that Heads of School – unless it’s directly connected to their mission – can and should recuse themselves from having to issue statements on really complicated, contentious issues.

When I gave an early version of some of these ideas, a member of my faculty said, “you know, I want to know where my Head stands on these issues.” And I said, you actually don’t need to know that to do your job well. I am aware of the podium the Head of School has, but I’m also aware of the way in which it can constrain the discussion of really complicated social and political issues.

The idea here is that Heads of School can support learning by being quiet sometimes. Not to mention the fact that I, as a Head of School, am not qualified to speak on all of these issues. I don’t have the kind of expertise one would need to speak on these issues, and I want to create a space for kids to express themselves.

Heads of School can support learning by being quiet sometimes. Not to mention the fact that I, as a Head of School, am not qualified to speak on all of these issues. I don’t have the kind of expertise one would need to speak on these issues, and I want to create a space for kids to express themselves.

Dr. John Austin

I think to some extent, the same is true with teachers. This is probably the most complicated piece of the Framework: what are the freedoms and obligations of faculty in terms of their own speech on campus? The Framework sets out a standard for that. It doesn’t say faculty are prohibited from expressing their own particular perspective or viewpoint in a classroom discussion, but it does say that faculty should exercise judgment and discretion when they do that, and they need to do it in such a way that it supports the autonomy of students.

The default for faculty is a principle of restraint, of asking questions, and of inhabiting different positions in the classroom. That’s not to say that faculty can’t have robust lives as citizens outside of school — they can. But it’s important for us to recognize the differential power between students and teachers. It’s our job to promote inquiry and curiosity, even when we feel really strongly and powerfully about something.

Liza: Yes. At R.E.A.L. ® we think a lot about how teachers can move into a coaching role during a discussion, rather than feeling like they need to be a player or, worse, a referee. I think tools like this Framework help folks zoom out and think about the big-picture goal. It helps faculty think: How does my voice land differently from the voice of everybody else in this classroom? What does it feel like for a student who agrees with me, or doesn’t, or doesn’t yet know what they think?

At R.E.A.L.® we think about teaching Discussion as a Discipline: it’s an art, but it’s built on foundational skills. Adults need to hold students accountable for developing those skills over time. This takes discipline and intention, certainly!

John: And the work you’re doing is really important, because helping faculty — even someone who’s been teaching for decades — develop the skills to support and facilitate this discussion of potentially controversial issues in American history or ethics, or wherever they happen across the curriculum, is really important. I think some faculty are frightened that they’ll leave their classroom and be subjected to some kind of criticism or hostility from a parent or someone else based on what happened in class. So I think helping faculty develop those capacities of helping facilitate discussion is absolutely critical.

Liza: Yes – to that point: the number one emotion we hear after R.E.A.L. ® trainings is relief. I think there’s so much power in stepping back and naming the challenges in the moment. It doesn’t matter if you’ve been teaching for two years or 22 or 42 — I think teaching in today’s world with today’s students requires new tools. We’re proud to work on that.

Let’s talk about the third pillar, Intellectual Diversity — another thing that won’t just happen spontaneously. What is intellectual diversity? What does it look like?

John: Intellectual diversity is a curricular challenge. How do you construct a curriculum that supports the exploration of a broad range of ideas and values and perspectives?

There aren’t any easy answers here. This is an area faculty can really lean into and think creatively and originally about how to accomplish that goal. I’ve always been a proponent of Gerald Graff’s idea that we should try to “teach the conflicts,” or try to structure curriculum as a conversation.

Any deep dive into a discipline will reveal that there are many ways to approach questions and have different debates within and beyond disciplines. Schools have an important responsibility of inducting and socializing young people into the idea of debate and intellectual difference and diversity. It’s really important for them, whenever they’re dealing with a question, to recognize first and foremost that there are different ways of approaching it, there are different arguments to be made about it, and that in order to make sense of those arguments, you first have to understand them. There are all kinds of opportunities for schools to think about what they’re trying to do with their curriculum.

Schools have an important responsibility of inducting and socializing young people into the idea of debate and intellectual difference and diversity. It’s really important for them, whenever they’re dealing with a question, to recognize first and foremost that there are different ways of approaching it, there are different arguments to be made about it, and that in order to make sense of those arguments, you first have to understand them.

Dr. John Austin

We need to challenge the idea of what Andrew Delbanco calls “intellectual affinity groups” — that is, moving kids from whatever perspective affirms their own worldview. Kids are literate. They can understand the idea of arguments, intellectual paradigms available to think about the world, and they can also be able to engage in those debates. We need to create a rich, diverse curriculum to support that.

Liza: I appreciate your naming all of this — and the work it will take to achieve true intellectual diversity. It strikes me that it’s important to think about curriculum not just from the content lens — the content decisions are infinite! — but also about the skills and frameworks that we can teach that can help intellectual diversity show up anywhere. With R.E.A.L.® we give students some anytime-anywhere questions they can ask (“Why are we reading this?” or “How else might someone think about this?”) as well as teaching older students to pull a piece of evidence as they prepare for discussion and interpret it in two different ways.

Our hypothesis is that exercises like that build, essentially, intellectual muscle memory. It teaches students to expect and elicit intellectual diversity. Once you’re comfortable understanding that every quote can be interpreted multiple ways, or you understand that you got stuck on one perspective because it resonated so deeply with your own lived experience, it’s easier to create a kind of intellectual agility alongside this diversity of content. How does that land?

John: I agree with you, and those skills you just mentioned are totally important. I do think though, that it’s very important and somewhat unfashionable at this particular moment in time to have a real, substantive conversation around content. I do think it’s time for schools to have those kinds of conversations, because the alternative is just an elective system based on individual faculty members’ particular interests.

Teaching courses that serve the intellectual development of the student and that don’t just happen to be something faculty are interested in requires sacrifice on the part of teachers. But there’s also an opportunity there to create really deep collaboration, thanks to the nuance you just pointed out about various interpretations of a single moment. Suddenly, if you have five teachers thinking through that question rather than one, you’ve created a better learning experience.

I think it might be time to think a little bit more about content to revive the idea of certain kinds of transformational texts that have real significance and enduring power in the world, so kids can have the opportunity to engage with those while coming together and thinking hard.

Liza: Yes — point well taken. The content question certainly deserves deep time and thought too. Perhaps a topic for another E. E. Ford Grant!

Now, we’ve talked a lot about ideals so far … what do you see as the biggest challenges to these ideals? I’m thinking about technology, teacher training, tools, too much pressure on schools in general, declining civility, something else altogether?

John: As a Head of School, there are some things that I can shape and control, and there are others that are completely out of my hands. It’s important for us all to recognize and embrace our spheres of influence: I’m not going to be able to impact the crisis in civility in the country. I can try to impact it on our own campus. In the end, all these principles come down to helping faculty live at the school. The faculty are ultimately responsible for the curriculum, for the tenor and tone and climate of the school, so providing opportunities for faculty to think through some of the instructional challenges that you’ve mentioned so beautifully over the course of this conversation, but also to think about how you’re creating opportunities for students to engage across difference, whether in or outside of the classroom, are just fundamentally important.

It’s important for us all to recognize and embrace our spheres of influence: I’m not going to be able to impact the crisis in civility in the country. I *can* try to impact it on our own campus.

Dr. John Austin

In that way, I think the challenge is getting faculty to row in the same direction. That’s never easy. Faculty are very fractious. They have very strong views. But we do need to think collectively about how we’re operationalizing these principles and these ideals across the school, not just in the curriculum.

Liza: Yes! That resonates with what I see in my work. When we partner with a school, a successful program is as much about balancing alignment and autonomy for faculty as it is delivering professional development or instructional coaching.

It won’t surprise you to learn that I spend a lot of time thinking about how face-to-face conversations feel different from conversing through a screen — particularly if you’re dealing with pluralistic contention of any kind. Could you riff on the ways in which tech complicates the ideal of “pluralistic contention”?

John: A lot of this has to do with the role of technology in schools and the “second curriculum” that is embedded in students’ phones through social media. Schools have to be kind of counter-cultural. Deerfield has made an attempt to have the kids leave their phones in their rooms. We try to create opportunities for students to fast from their phones. I think that’s really important, because as you said earlier, the way in which you engage through social media and communicate with others is very different from what happens when you engage with someone face-to-face. Schools have the opportunity and privilege to have face-to-face interactions, which create trust. I think schools need to get a handle on that.

The way in which you engage through social media and communicate with others is very different from what happens when you engage with someone face-to-face. Schools have the opportunity and privilege to have face-to-face interactions, which create trust.

dR. jOHN aUSTIN

I like to think of the culture of a school as a series of knobs that you turn up and down. I think schools need to turn up forms of prosocial face-to-face connection. They need to turn down the stuff that gets in the way of that.

We do imply in the Framework that on the one hand, schools need to get a grip on the phone situation, because it’s not good for kids socially, emotionally, intellectually, but at the same time, we’ve got to be attentive to how things like AI are going to change how we operate. In schools, we don’t have answers to that yet — but we’ll need to figure it out.

Liza: Indeed! So, John, this Framework is primarily aimed at independent secondary schools. Are there elements that you see as relevant to educators working with younger students or in different kinds of schools?

John: It’s not written for college students, though I can imagine it might be useful for some colleges and universities, and it certainly wasn’t written for elementary-aged kids. The developmental sweet spot is for high schools.

Middle school might be a place where this would land quite well. But the Framework is grounded in the idea that kids of that particular developmental stage require a certain kind of educational environment to unlock their minds, their curiosity, and their independence of thought. The hope is these principles speak to that and will help schools create that kind of environment.

Many different kinds of schools — public, private, charter, religious — are doing amazing things, and many schools have a tradition of debate and dialect. There’s a lot we can learn from them, too.

Liza: Yes — I certainly see how expressive freedom, disciplined nonpartisanship, and intellectual diversity feel most relevant to the developmental phase of high school. But I do think that schools can teach these values and skills — perhaps with slightly simpler language! — well before age 15. At R.E.A.L.®, we think of teaching discussion like teaching a sport. In Lower School, it’s learning discrete skills: how to dribble, how to shoot, how to pass … or how to ask, how to relate, how to listen. Then in middle school, it’s how to scrimmage: What are the rules of the game? How do I get my voice in? How do I make space for others? What do I do when I’m not talking? What happens when people disagree? And then in high school, it’s truly student-led — students have the skills and know the rules of the game, so now they get to run and lead plays, reflect on team dynamics … and the teacher moves into a coaching role. It’s clear to me how your language is perfectly oriented for high school teachers to use as they “coach” students in discussion.

Thank you so much for joining us, John. This was a wonderfully mind-bending discussion about discussion on campus in today’s world!

John: That was great, Liza. Thank you, and thanks for all your great work.