Why Asking Matters: A Conversation with Jeff Wetzler

Jeff Wetzler is the co-founder and co-CEO of Transcend, an organization that strives to support school communities as they create extraordinary, equitable learning environments, and the author of Ask: Tap Into the Hidden Wisdom of People Around You for Unexpected Breakthroughs in Leadership and Life. What follows is a conversation between Jeff and R.E.A.L. ® Founder Liza Garonzik. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Liza: Welcome, Jeff. We are thrilled to have you here today. We’re so excited about your book, Ask: Tap Into the Hidden Wisdom of People Around You for Unexpected Breakthroughs in Leadership and Life. When I first came across your work, it struck me that what you’re doing is essentially R.E.A.L.® for adults. In our model, we have these four skills: relate, excerpt, ask, and listen. Yours is a book dedicated entirely to asking, and to helping adults have better conversations in their lives and workplaces.

So thank you for being here. We’re so excited to be thinking about how to make discussions better for adults as well as kids. But first, tell us about your path into education. What have you done, and what led you to write this book?

Jeff Wetzler: My path into education probably started well before I got into the business world, and the common theme has been learning no matter the context. When I was a kid, I was always interested in teaching and learning. I was always thinking to myself, if I were the teacher, what would I do here? How would I make this even more engaging for myself and my peers? I did lots of teaching to younger elementary school students through a program at my high school, and I continued that in college as well. The education path has always been in me.

I then spent almost a decade at a place called Monitor Group, which was a management consulting company whose motto was “a place for optimists to change the world.” They placed a huge emphasis on how learning happens in organizations. There was a professor there named Chris Argyris, who focused on why it is that sometimes the smartest, most “successful” people are the worst at learning, especially the worst at learning from one another – in part because they’ve often been rewarded for giving answers that are right, as opposed to asking questions. That really drew me in.

It was there that I really started to get the seeds of the book Ask. And while I was there, one of my clients was Teach For America. I consulted to TFA founder Wendy Kopp for five years, then she asked if I would help come run part of Teach for America. Initially, I did that as a two-year leave of absence from Monitor. Once I was inside, doing the work in the field of education, I was in love, and I stayed there for a decade.

Liza: Amazing. And then after TFA, you built Transcend, right? Can you tell us about that?

Jeff: At Teach For America, most of the time my role was responsible for training and supporting TFA’s thousands of teachers across the country. Every year we worked on how to improve the training and coaching and support, and every year we’d make progress on things like lesson planning or checking for understanding or various different skills, but we weren’t seeing transformational changes in teacher performance.

I started thinking, maybe there’s something beyond the training – maybe it has to do with the way teachers’ roles are designed. It’s such a difficult situation our teachers are in. It would almost be like saying to doctors: you have to be the general practitioner, and the nurse, and the X-ray technician, and you have to invent the drugs, and see 30 patients at the exact same time, and every one of those patients has a different thing going on – and then if the performance wasn’t excellent, somehow the right answer would just be to train the doctor better.

That is kind of the situation teachers are in. When I started to think about that, I thought, maybe we need to look at why the teacher role is designed the way it is. When I pulled on that thread, I very quickly got to: why are classrooms designed the way they are? And then, why are schools designed that way? And then, why has that not changed in 100 years? And what impact does that have not just on educators, but on young people? That industrial design of school isn’t really designed to encourage young people to ask questions or be curious – it’s designed to encourage them to give answers and comply.

All of that fired me up to say: what if we applied the best of design thinking and learning science and R&D methods to support communities that want to design radically better learning environments? That was the motivation to start Transcend.

We initially piloted it in a small setting, and we saw some really promising outcomes and experiences not just for young people, but for educators too. We thought communities everywhere deserve this – but we didn’t see enough capacity in the field to support schools to do this kind of intentional design work, and it felt like maybe there was a need for a new organization.

Liza: One of the things I love so much about your story is that questions motivated each move you made! You stepped back and asked “why” before you made your next leap – which just goes to show exactly how powerful asking is.

I think we all know that being good at asking questions is an important skill to have. Nobody disagrees with that. But why is asking questions so important? One thing we hear a lot from our R.E.A.L.® teachers is that they want to make every voice heard in their classrooms – and in your book you begin by actually laying out the research behind the impact of people not feeling as if they’re able to contribute. Can you tell us about the research you encountered on how question-asking can be a tool for inclusion?

Jeff: The first thing I would say is that it’s incredibly pervasive, how often people’s voices are not heard. I focused on primarily adult settings in the book and came across staggering statistics – upwards of 80% of adults in organizations are not having their voices heard.

It’s incredibly pervasive, how often people’s voices are not heard.

JEFF WETZLER

I would venture to say this is true in schools: for people to have situations where they were concerned about something that they did not feel safe to share, or had an idea or suggestion for improvement.

Even in our personal lives, there was one fascinating study that talked about how somewhere between 60 and 80% of people withhold what they’re really thinking from their own doctors. If we’re not even telling our own doctors what’s real for us, when our lives could be at stake, how much else are we holding back?

So the first research finding is that it happens all the time that people silence themselves or feel silenced. The kinds of things that people hold back include their greatest struggles and challenges, feedback and observations, wild and crazy ideas that might just be game-changers, but which people think are too crazy to share.

I also looked at some of the biggest barriers to why people are withholding. The number-one barrier was fear of the impact of saying what they would have to say. Maybe if they tell us what they’re really thinking, we will be hurt or upset, or maybe we’ll punish them, or maybe it will create tension. And our students are afraid of being canceled.

The number-one barrier was fear of the impact of saying what they would have to say. Maybe if they tell us what they’re really thinking, we will be hurt or upset, or maybe we’ll punish them, or maybe it will create tension. And our students are afraid of being canceled.

Jeff wetzler

Liza: Absolutely. That’s how it manifests in the middle or high school classroom today: fear of being canceled by their peers.

Jeff: I can completely see that. And I would venture to say that teachers may be holding back out of a similar fear.

One of the biggest reasons people hold back from telling us what they’re really thinking or feeling is that they don’t realize that we’re interested. And that’s sad.

None of this would be a problem if we could just read other people’s minds. There’s really interesting research on that, including by a researcher named Nick Epley, who talks about how unlikely it is that we can actually know what someone else is really thinking and feeling. Even if we follow some of the most common advice – like reading body language or empathizing – it doesn’t reliably work. The only thing that his research found that reliably works to know what someone else is truly thinking and feeling is to ask them. Ultimately, very few people are taught how to ask questions.

The only thing…that reliably works to know what someone else is truly thinking and feeling is to ask them. Ultimately, very few people are taught how to ask questions.

Jeff Wetzler

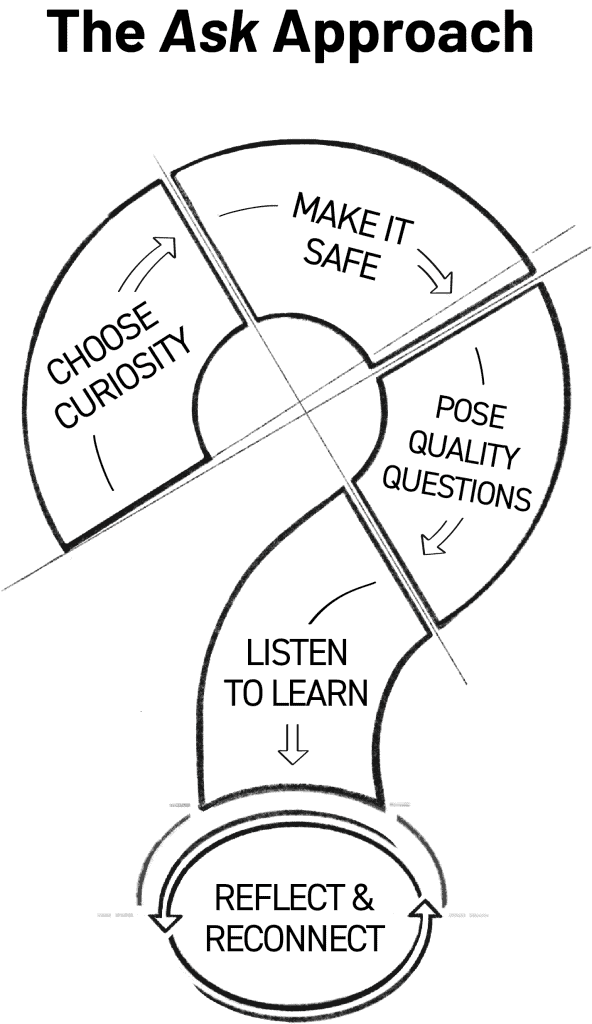

Liza: So how do we do it? What’s your advice on how to ask questions? I know one of the starting points for you is to choose curiosity: rather than make an assumption, be curious. What are ways people can do that and communicate their interest in their conversation partner?

Jeff: A lot of it is actually about questions we ask ourselves. The single most helpful question we can ask ourselves if we’re trying to awaken our own curiosity in an interaction with someone is: what can I learn from this person? Sometimes that can push away any other noise that gets in the way of curiosity.

There are other questions we can ask ourselves, like, simply: what might I be missing? What am I overlooking here? Or, how might I be contributing to the challenge that we’re trying to resolve? What impact might I be having on the other person?

In the book, I talk about a number of what I call “curiosity questions,” which are questions we can ask ourselves to inject question marks into the otherwise certain stories we often carry around, and which can keep us from being curious.

Liza: I love that idea of injecting question marks. In R.E.A.L.® discussions, the conversation is driven by DQ’s, or discussion questions. Sometimes, in a student-led discussion, the DQ starts dying because everybody is certain they’ve answered it; they’ve arrived at a conclusion … but they still have four more minutes of class. We teach students to handle this situation by “injecting a question mark” … we tell them there are two questions they can always ask. One: how else might someone think about this? And another: why are we reading this?

It’s amazing to watch how giving kids a template to question-asking unlocks so much for the whole group in a moment when they might otherwise be uncomfortable.

Jeff: I love those questions.

Liza: So the second big category of advice you offer in this book is really around listening to learn. What does that mean?

Jeff: There is a really big distinction between the listening we think we’re doing versus actually hearing what’s most essential for someone. Most of us think we’re better at listening than we actually are.

Most of us think we’re better at listening than we actually are.

Jeff Wetzler

In research for the book, I interviewed professional listeners in the form of journalists, who are constantly asking questions and listening. One of the themes I heard was how much they miss, even as professional journalists.

I remember talking to Jenny Anderson, an award-winning journalist, who told me she records conversations whenever she can, and then she goes back and listens again and again and again. Each time she listens to the conversation, she hears something she missed the previous time.

If a professional listener is missing that much every single time, how much are the rest of us missing? In the book, I talk about the importance of broadening the channels we listen through. Many of us are taught to listen for the content of what someone is saying – the facts, the figures, the information, the claims they’re making. But there are two other channels that matter a lot as well.

One channel is listening for emotions. What feelings are being expressed and displayed in the conversation? Also, what are the actions that people are taking? Are people repeating themselves? Are they asking for help? Are they pushing back? That’s another channel to listen for – the action.

So content, emotion, actions. In the same way that great musicians train themselves to listen for the percussion, and the harmony, and the vocals, we can train ourselves to listen for a richer set of information – and almost triple the amount that we’re learning if we listen through all three channels.

In the same way that great musicians train themselves to listen for the percussion, and the harmony, and the vocals, we can train ourselves to listen for a richer set of information — and almost triple the amount that we’re learning if we listen through all three channels.

Jeff Wetzler

Liza: Something we see when working with students is that kids generally say they’re good listeners. But one exercise we do is take a “time out” during every discussion where kids have to write down something they heard a classmate say, then explain how it changed or challenged their thinking.

We reliably find that no matter how old the kids are, this is a challenging task at first – to your point, they aren’t really listening to each other. By about two discussions in, when they know they’re listening not just for the content of what someone said, but they’re also thinking through why it matters and how to respond to it, our data show that students suddenly feel as if they’re much more active listeners. Their notes get longer. Their examples get more specific. Their responses get more honest. I love the idea too, that you need to listen to learn, but you can also learn to listen better.

Jeff: One of the best ways to both listen to learn and learn to listen is to go back to the other person and say: ‘this is what I think I heard you say. How well did I hear you? What did I miss?’ That is both a way to demonstrate that we’re trying to listen and to correct our listening. When I do that, at least half the time, someone will say, ‘well, you got this part, right. But there’s something more.’ That enables me to better tune my listening.

Liza: It’s also a gift to give the speaker another chance to articulate themselves. In a world that moves so fast, it really slows things down. Asking to listen is important – and human.

Jeff: I totally agree.

Liza: At R.E.A.L.® we’re very big on toggling between the micro – mechanics of discussion – and the macro – the aggregate impact of discussion skills in our world. What do you see as the reason that asking matters so much? And secondarily, why does asking matter in the world of education?

Jeff: We are living at a moment in time in our broader society where we understand each other less and less. Technology isolates us, and we’re living through a heightened level of division and polarization in our society. I think so much of that comes from assumptions we make about each other, and a lack of true curiosity, questioning, and listening.

One of my hopes – and this is where I end the book – is that if we can build the desire and capabilities to truly orient every single person to the idea that we can learn from one another, then these skills of asking and listening might play some small role in healing some of the divisions that I really worry about in our time right now.

When we do that – and I’ve seen this in my own life and experience – we realize we’re not as different as we think we are. We realize that we do share a common humanity, and that we share so much more than we don’t share. That’s my hope for the place of this in the broader world.

As it relates to educators: one of the greatest things we can do for kids is to be models of the kinds of learners we’re hoping to cultivate. One of my favorite quotes, from James Baldwin, is that children have never been very good at listening to their elders, but they have never failed to imitate them. If we want to raise curious question-askers, then we need to demonstrate what it looks like to be a learner. We need to model saying: “that’s an amazing question. I don’t know, how would we find out?” We need to show that we can be curious. I think asking questions might be the single most powerful move we can make in terms of education for kids.

One of the greatest things we can do for kids is to be models of the kinds of learners we’re hoping to cultivate.

Jeff Wetzler

Liza: I love that – and I think it’s also important to ask great questions of students themselves. One exercise we do in our R.E.A.L. ® training explores various reasons students might be quiet in class, and it’s the product of an experience I had when teaching high school English. I had one girl in my third period class who was an introvert who had learned to be a consistent and deep contributor to discussion, but there was one day close to the end of the school year when she didn’t talk at all. I went up to her at the end of class and asked, “Why are you so quiet today?” And she said, “I really didn’t agree with something that my classmate said. I was sitting there deeply trying to understand how he arrived at his perspective, and I didn’t feel as if I got to that place. I wasn’t sure I had something to say to him yet, but I was thinking about bringing it up next class.”

As the teacher, I was speechless. All it took was my asking one question to uncover a deep level of metacognition, empathy, and true non-verbal engagement. I always try to remember that asking is not hard, and it doesn’t take long – but man, it can be powerful.

Jeff: Oh, I love that. There’s so much we could unpack about what you did that matters in terms of your curiosity and making it safe and choosing the right moment and listening and all that. And I think you’ve obviously illustrated yet another important reason why it matters for teachers to be asking questions: to understand students.

Liza: Absolutely. And I think there are a zillion questions teachers can and should be asking about what great teaching looks like in today’s world and tomorrow’s -– which is part of your core work at Transcend! Thank you so much for being with us today, Jeff.

Jeff: This was incredible. Thank you so much.