Protagonists: David McCullough

Founder of the American Exchange Project

What is the American Exchange Project, and how did you first come upon the idea for it?

In short, we’re building a national domestic exchange program for high school kids. This program would allow any high school senior in America to travel abroad in their own country for free in the summer after they graduate. We think it would benefit tremendously the strength of our democracy and the development of our nation’s kids, if every student received, with their high school diploma, a ticket to town that’s completely different from the one they grew up in. We’re taking that dream and trying to make it a reality as part of a larger effort to figure out how Americans from different backgrounds, with different beliefs, can develop empathy and respect for each other. We’ve been at it two years, though the pandemic has prevented us from actually traveling, of course.

Our story began in several different places. For years, Paul Solman of the PBS NewsHour has been trying to do something like what we’re working on now. Paul’s chief observation across the last thirty years reporting on our economy is that inequality is increasing and groups of Americans, as a result, have been growing apart from each other. Because of that, it’s hard for people to understand one another. Solman found ways to get people from different backgrounds interacting as people, bringing together folks from both sides of that divide to have real conversations and help people come back together. Whether going to Appalachia with friends from New York to talk about healthcare or bringing Yale professors to Gateway Community College, he’d long had the idea that an organization should exist that could take people from different backgrounds and put them in same room.

Fast forward to 2016, I was a junior at Yale and part of a program that gave me a summer fellowship to do basically whatever I wanted. I love road trips and I was very curious as to why schools in poor areas were so often having a hard time. Why was there such a disparity in the quality of public education between rich and poor towns? And when I read up on the issue, I found that there were hardly any people talking to folks in the middle of it, teachers, students, administrators, parents. I was an American Studies major, and I’d learned in this tradition of people taking the experiment on the road: James Agee and Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Alexis De Toqueville, and so on. I took the fellowship, borrowed my mom’s Mazda, and hit the road. I traveled to Cotulla, Texas, the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota, and Cleveland, and I talked to everyone I met: Students, teachers, the barber, the medicine woman, the preacher, anyone. And this “study abroad” in my own country quickly became the most profound educational experience I’d ever had, and I came away with great research and, much more importantly, great pals who could not have been more different from me. In fact, about two months after the trip, a few of my Cotulla pals came and visited me. I wrote a paper about the whole trip for the course. Now, Paul was a guest professor in that course and he read the paper.

Two years later, after I finished graduate school, I called up Paul [Solman] to have lunch and talk about what I should do with my life. At that lunch, we both talked about our experiences traveling domestically. We had the idea: what if we had an organization that helped people do the same thing. Right away, my heart told me: “this is what I want to do.”

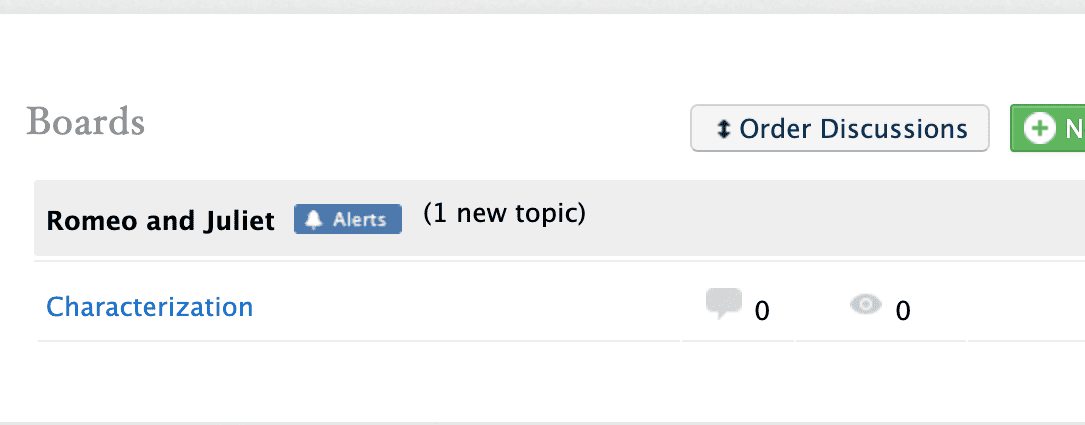

We brought in some friends and connections and started to do “market research” on what was out there. At the time, I had about $43 in my savings account, so I needed a job. The only job that would let me off when I had to prioritize this nonprofit was substitute teaching at the high school I went to here in Sudbury, MA, a largely liberal, white collar town. I got a job as a substitute in January 2019 and would work on my laptop on this nonprofit while the kids were busy with whatever lesson I’d been told to administer. I also coached baseball and generally came to know students well. In the spring, I ended up talking with some students about AEP. I’d pitched to academics and investors, but I’d never talked to kids about it. So I put together this rudimentary lesson plan about division in America and the road trip that started it all, and I noticed that kids really stopped and listened. They were fascinated by these far away American towns that were completely different from Sudbury: Cotulla, Lake Charles, LA, Davenport, IA; they all started asking these sophisticated questions unlike what I’d heard from them before.

They said they felt like they were growing up in a bubble. Now that set off the light bulb. In 2016, driving around the country, I heard kids in towns that were the American opposite of Sudbury say the same complaint about their towns. Kids on opposite sides of society were saying the same thing from opposing places. And they were saying it because it’s true. Kids today are growing up in bubbles, different bubbles, yes, but bubbles just the same. They aren’t really exposed to variety and difference in this country, and it’s the product of the inequality and polarization that’s causing so many of our nation’s other problems. I called up Paul and Bob Glauber, a Harvard professor and another close advisor to us, and we thought, why not just have them switch bubbles? And that’s how we landed on the idea.

How do you think that this program promotes dialogue and discourse in the US in a new way?

First, “a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down.” AEP focuses on fun and curiosity. Teenagers connect over questions like: “How do you do this thing we do where you are?” Everything from “what is gumbo?” to “what about teen pregnancy in your community?” is fascinating to these kids. We want to create an environment in which they’re organically having these conversations; we want to facilitate the interactions they’re missing and then let them take it from there. Eighteen year old students are so aware when they encounter something new. Most kids really don’t need coaching. They just need the right environment. It’s curiosity that’s driving these conversations. We don’t have a six step process toward understanding someone different from you. We have one rule on our AEP hangouts: be nice.

During those conversations, kids realize a lot about the diversity in our country and a lot about themselves. In the beginning, we’re sitting on Zoom with seniors from Concord, MA and seniors from Lake Charles, LA. They don’t know what to say or what is distinct about the places in which they live. By the end of the program, they’ve learned a lot about their own towns in the process of telling others about it. They’re exposed to lifestyles, norms, views not in their own communities, but they’re also exposed to themselves and their positions in American society. My grandfather once told me, “When you travel abroad, the country you learn the most about is your own.” There’s a little of that going on in our conversations. So kids gain firsthand exposure to new places, ideas, and ways of life, and they’re also able to understand a bit more about their own towns. In a way, these conversations contextualize who they are and where they’re from.

How does your program and team foster “cross-cultural” exchange? If we look at (hopefully) a future of less segregated schools, what does it mean to structure those exchanges and experiences to make that learning happen?

There’s a laundry list. First, again, we have to focus on fun — yes, you may talk about the issues in a community, but you also have to talk about the great sandwich shop and or the famous pizza place everyone who visits should try. Second, we try to get the kids telling stories about points of pride and pain. A lot of issues with kids, rich or poor, liberal or conservative, revolve around self-esteem. I think both our democracy and our kids could use a little more self-confidence and encouragement to be themselves, to own what’s great about them. We need to level the field by focusing on the fact that every kid on the exchange (or, now, on the Zoom call) has something to learn and, more importantly, something to teach. This surprises and delights most kids, and it gets them talking.

Our kids grow up in what is supposed to be a meritocracy, but wealthy kids are armed to succeed in disproportionate ways. That’s unfair, and from what I’ve seen, those kids who are behind in the race, or from low means, more often feel bad, or left out, not good enough, than angry. We see it every day in our program. We see it in what people do over the summer. Joey prefers Florence over Milan, while Hannah from Idaho has never been out of the state. Little things like that quickly turn into big things for kids. Once kids see that difference, it’s complicated to address it. So we try to create an environment in which there’s no real hierarchy.

Vocabularies are also connected to power. White kids from the North will tell Black kids from the South how they should feel about the Confederate flag using academic language that seems to give them power and authority that isn’t earned or necessarily productive. Sometimes conversations will compare the cost per square foot of a house in different places, and the difference is astronomical. How do you create value and self-worth with the American economy the way that it is? I don’t have an answer to that question yet, but we try to work on it.

We constantly have to balance in loaded situations. When someone from the North says “the south is racist” we point out that Boston was voted the most racist city in the country a few years ago. “Conservatives have policies that are backward” — a lot of liberals do, too. We all often need to be humbled and reminded of transgressions that happen in our own backyards. “Smart” isn’t something that you are or aren’t, just like “right.” We’re all capable of smart and dumb, right and wrong, and we’re both all the time, so instead of putting each other down or proving each other wrong, we ought to be curious about one another. We ought to learn. That’s what we try to show the kids.

We had a call about a year ago with a number of kids. Chris is your poster-child kid, kind of looks like Captain America, from a wealthy town in MA. John is from Louisiana, an industrious hardworking kid who doesn’t go to school in the fall because he helps his dad hunt alligators. He didn’t want to go to college; he wanted to go to work and make money. Now, he’s done all that and bought a house at the age of 18. On a call last year, he was on his back fixing his truck while Chris was sitting up at his desk. In the middle, I asked what John was working on, and he said “the transmission.” I asked Chris what a transmission was and he had no idea, even though he drives his car 3 or 4 times each week. John taught Chris. Through conversation, we can challenge kids to reassess and reallocate what knowledge is and who holds it. Kids have great BS detectors and will understand when you’re trying to make them feel valued through ways that are contrived. So, instead, we try to tap kids interests, to let them show off their enthusiasms. The best way to do this, by far, is getting kids to show and not tell, and when they do tell, to tell stories.

One thing that we like to do is the six word story; tell your life story in six words. Or we have people bring in items from their desks that mean a lot to them and then talk about them. Kids are much better at these conversations when they are focused on activity, some simple project they can work on together. And more often than not, they do it naturally. I saw this when we held our first ever hangout. It was with kids from Louisiana and Massachusetts. I told them: “you’re going on a road trip. You can choose three destinations, and you can bring a famous person from now, a person from history, and a person no one else in the hangout knows”. Right away, the kids started planning the same road trip together, even though I’d initially thought they’d do it independently as an icebreaker. Immediately, they had to figure out where they wanted to go, and who knew what about different parts of the world. Soon they were delegating and googling how far it is to get a ferry from Japan to South Korea. They ended up working together to determine where to go. Then they have to pick who makes it into the car. This gets interesting. History shows cultural difference. More often than not, kids from the North want to bring Lincoln, and the kids from the South wanted to bring Jesus. Then the living celebrity shows the cultural icons we share; Kevin Hart gets the nod a lot here. Finally, the third person in the car tells kids something about themselves, and it requires them to negotiate civilly. They have to choose whether my aunt should go over your aunt. It’s the perfect icebreaker for us to bring students together. It’s focused on fun, not on loaded questions or governing rules. And I hardly had to say a word. The kids did it all on their own. We’re just creating a great environment, a playground for conversation, early on. Instead of six-step lesson plans, we try to build playgrounds, the monkey bars of civil dialogue- structures that mold action while inspiring imagination and group play.

What are some of the barriers to great discussion and communication that your students encounter when they leave a familiar context?

I think the first barrier is the kid who talks too much. The second barrier is the kids who are trying to prove something, especially how smart they are, at the expense of others. The largest barrier is that rich kids make poor kids feel dumb and liberal kids make conservative kids feel racist. Those are the biggest conflicts we see. Also, kids from privileged backgrounds have more free time, generally. It’s harder to get kids from more adverse circumstances joining after school. Then, you have less productive conversations.

The other barrier too is for BIPOC students, because if they aren’t represented in the room, then many are generally very hesitant to tell stories. Being the lone minority, of any kind, racial, geographic, economic, in a room is incredibly difficult on the student, a huge weight, and it cultivates a lot of resiliency, but also loneliness. An unfortunate reality right now is that a lot of communities and schools in politics and policies become very homogeneous, and kids can become really tribal. This makes it worse. We have an open Zoom room right now–like an online cafeteria–with set topics. At the beginning, we had lots of kids from all over joining, it was great. Over time, a clique kind of took it over. A certain group of kids with consistent viewpoints showed up and took it over. It’s become a gathering place for them. This tendency, of kids feeling marginalized, left out, or behind in the race, is by far the largest hurdle in these conversations.

How is the kind of connection you foster different from the kind of connection kids can find on social media?

It’s a more genuine and realistic version of social media. You’re there with another person on a screen and it’s as close to a real communication as possible. We work out of the lack of connection that kids feel from the bubble, polarization, and the negative influences of social media. Social media draws kids in with their curiosity, but it becomes disingenuous and plays into the lesser angels of our nature. Like social media, we want to create more connections, but we want the interactions to be more genuine and real by actually bringing people together. To show them the full dimensions of a place and a person, to allow them to actively interact. Our belief is this will help grow substantive networks and boost confidence, two characteristics our kids are short on today.

It seems like the step of reflection is also a difference.

There’s a difference between saying something when you want to be heard and saying something when you’re asked. You post because you want to, not because someone else has said they’re curious about it. At AEP, you’re surrounded by peers who are there because they want to learn more about you. That’s a fundamental difference between us and social media.

What’s a prediction you have for the future of education?

I’m optimistic because everywhere I travel, I meet wonderful people who are involved in education. There are wonderful kids, and there are wonderful people are becoming educators. By and large, we are a nation of good people who care about the right things. Kids come away from our calls saying much more unites us than divides us. The future of education has to help students, and our nation, discover this.

Education should be more interactive. It should emphasize curiosity above grades. “What’s your GPA?” is a very personal question to kids now. But I tell students the only bad GPA is the one you become obsessed with. We should prize independent thought and independent ambition more than we do, and we should help kids cultivate curiosity above anything else. I worry that education is becoming too much about the grade, the test, and whether you’re in advanced placement, advanced college placement, or advanced honors A-List college placement. I worry that kids today don’t feel the freedom to discover, to follow a passion, to fail and get back up again, or to wander out of the bubble or away from the rail tracks. I think this has created a crisis in confidence among kids that spans the country. Schools ought to help kids move away from this. I took AP history sophomore year and it was rigorously taught to the test and I was mostly miserably chasing a grade. And I loved history. After the AP test, in the three weeks before school ended, when there was no AP curriculum left to do, it became my favorite class. Our task was to write a a paper about whatever we wanted. I wrote about Benny Goodman’s performance of Sing, Sing, Sing at Carnegie Hall in 1938. I still love that song. I’d probably fail the AP Test if I took it right now, but I still listen to Sing, Sing, Sing, and now I’m involved in a huge experiment trying to promote a version of mass experiential culture education in America. Jazz bridged divides the way AEP is trying to.What does that tell you about the nature of education?

I think kids learn the most from their experiences, the things they do, the things they actively pursue. We gain the most from trying something new, something that little whisper of curiosity in our chest compelled us toward. And when we stick with it, these wonderful things come to shape our lives. Our schools do a great job of cultivating these moments for most kids, but they ought to keep going. This will create more engaged and enlightened citizens.

This needs to be the future of not just our education system, but our country at large. To inspire our citizens to become more engaged, to earn back our faith in democracy and our faith in one another. Our democracy is in dire straits and our education system will not only help lead us to safety, but it can also ensure that we remain there.

My prediction is that we’ll get there, but we have to act, we have to get involved, we have to roll our sleeves up and find solutions to these intractable issues of tribalism, inequality, and polarization. And I can think of no better group of people to lead the way than our nation’s students.