Office Hours Interview: Suniya Luthar and Nina Kumar of Authentic Connections

It was our pleasure to meet Nina Kumar and Suniya Luthar, co-founders of Authentic Connections, for this week’s Office Hours. In our interview, Nina and Suniya share insights from their research and work with schools to make positive interventions in student and teacher mental health and belonging.

Authentic Connections is currently offering any school its first Resilience survey cost-free. Reach out through the Authentic Connections website to connect your school.

We’re so excited to talk with you today. We love and admire your mission: at REAL we’re all about reflecting upon our practice as educators, redefining what success does and could mean for teachers and identifying strategic practices to enhance inclusive and safe learning environments. Authentic Connections has certainly emerged as an important resource for schools hoping to achieve similar ends. How did you come up with the idea for Authentic Connections, and how did you begin to engage schools in your work?

Nina Kumar (NK): Authentic Connections was really built to help improve mental health and wellbeing in schools. Everything is based on Suniya’s three decades of research on resilience. We wanted to bring as much of that research into schools as we could. I could see the impact Suniya had in individual schools. Her data and the access they gave to student voices was allowing schools to shape the way that they used programming and teaching to focus on wellbeing. So we founded this organization to help as many schools as possible to use data to make decisions that are best for the community.

Has it changed the process of bringing data to schools changed in any ways?

Suniya Luthar (SL): My own Ph.D. mentor, Ed Zigler, taught me that when studying children and families, we owe it to them to bring that research back and create positive change from it. Since my dissertation work in the 1980’s, I would work with one or two schools in a given year. Once Nina got involved with this process, she developed web-based ways to do assessments in ways that are scientifically rigorous, and at the same time, streamlined and efficient. She also developed interactive dashboards which could be used to convey major findings to stakeholders in easily digestible, clear, and granular ways,. Eventually, in the process of partnership with each school, we are able to come to very specific recommendations that are based on their own data, along with action plans. And it’s Nina’s sophisticated data management strategies that have made all this growth possible, helping greatly to expand our reach.

What key questions, interventions, and areas do you look to gather information about student well-being, especially within the classroom?

NK: Most of what we’re doing in class has to do with students’ relationships with teachers, teacher’ relationships with other teachers, and students’ relationships with one other. There’s so much work that’s been done around pedagogy and what’s been done with how students learn, but we go beyond that, trying to look at relationships. We know that resilience (or doing well despite stress) rests on relationships, so if we want kids to learn well, we need to make sure that they feel supported, We look at the various dynamics that significantly impact students’ ability to learn.

SL: The same holds true for the adults– going back to Ed Zigler, he talked about working with the whole child, not just their test stores and standards. In the same way, we have to pay attention to wellbeing of those who take care of the child, at home and at school. You can’t have adults doing all that’s required of them if they themselves are not adequately cared for.

Especially right now, during this pandemic, it seems like that care and well-being for adults is at risk.

SL: I just did an interview the other day with a journalist talking about teachers and parents taking care of themselves. And I clarified yet again that I am not talking about self-care; I’m talking about adults being taken care of. We often say teachers and parents’ jobs are to take care of the younger generation; at the same time, it is important to deliberately ensure that the adults are taken care of, and this is a lifetime need. So in our work with schools, we’re not just assessing burnout among teachers but also the kind of relationships they have, the kinds of support they have, and so on. The important question is, How about you — as a teacher and human being, how do you feel? As an LGBTQ individual? As a person of color teaching in a school where you otherwise don’t feel represented? How safe do you feel in your closest relationships? Understanding all this is important because if you feel unsafe in close everyday relationships, it affects everything you do.

What do you think are the biggest blind spots that teachers have that get in the way of heightening students’ sense of belonging and voice in their classrooms?

NK: The thing that we hear most often is that in schools, aspects of relationships that are negative have a stronger impact than the positive ones. Feeling embarrassed, for example, has a bigger impact than hearing positive things, even though many teachers and schools work so hard on giving kids emotional support. That surprises people, to hear that even if we don’t intend for negative interactions to come off harshly, when the person on the receiving end perceives it as harsh, it has a huge impact. That’s one thing. Also, during this pandemic time, at the start of distance learning, schools were often surprised that students felt conflicted about turning cameras on during Zoom class. The pressure to put cameras on, made some kids feel uncomfortable, because they didn’t want others to see where they lived. Obviously teachers want kids to feel included, but for some students that backfired, and it made them feel unhappy when singled out in this way.

SL: I’ve been running these groups or circles online to connect people in leadership during the pandemic. As Nina said, one of the surprises for people is that when you think about fostering resilience, many educators think that means a focus on more positive things in relationships at school. The data say, though, that we need to focus first on minimizing unkindness in the community, for students as well as adults at school.

What’s concerns me deeply is that the longer the pandemic goes on, the more frail we become, and the more distanced, closed up, or irritable we can become in our close relationships. My goal in running these circles and groups is to thwart that, and bring people together to keep the fabric of community as strong as possible. At the same time, I must say that it’s not easy to do, what I’m asking. Would it be easy for you if I asked you what’s really weighing on you? As gentle and kind as I may be toward you, it’s scary to be vulnerable. So paradoxically, we all need to be open and honest and share what’s going on with us, but that’s the hardest thing to do. The more upset we get, the more we tend to shut down or become touchy or overly sensitive. I don’t think that people have understood this; there has been much talk about general, generic stress, but not much about how much this has been damaging close relationships.

When teachers and educators are feeling that sense of exhaustion and lack of outlet for emotions, it can be hard to generate energy. In an online or hybrid classroom, a teacher actually ends up needing to give much more energy to make class happen, because it’s also hard for the students to bring energy.

SL: We’ve found that in the faculty/staff surveys, what’s most often mentioned in response to questions about what’s going well and what needs improvement, are two themes: 1) expressions of concern for teachers from administrators; and 2) feelings of connection with colleagues. Having a community of colleagues keeps you grounded and anchored. So for those who are teaching from home, it can become isolating, being without that source of energy and connection. Even with the anxiety of infections when teaching in person during the pandemic, the psychological support of in person interactions can be incredibly helpful.

On IRT, we’re focused primarily on student discussions. We operate on the premise that teachers can and should adjust their practices for the students of the 21st century. When you imagine an effective student-led discussion in the 21st century, what does that mean? What are the biggest opportunities teachers have with students now, specifically, that they haven’t had before; conversely, what are the new challenges?

SL: One of the challenges now with the pandemic is making sure that kids are engaged and making sure that certain kids don’t feel left out. It’s easier for some students to fall off the radar right now. In terms of what to do when students come back in person, there are a couple of things that may be helpful. Pedagogically, educators need to engage students so that they see, as far as possible, the relevance of materials to their own lives. If they can discuss issues in ways that are personally relevant to themselves, it can make the conversation more lively and help the students feel more engaged. Also, teachers can use themselves as role models. In the first classes that I myself taught each semester as a professor, I would tell the class that I myself was terribly shy and tongue-tied as a student; if they’re looking for a way to be more active in class, they can start by simply raising their hands and just asking for material to be reframed. We need to understand that some students are shy, some students aren’t, and as teachers, we need to just communicate, sincerely, that we really do want to hear their voices.

In many ways, really, it boils down to articulating that same care we’ve been talking about.

SL: Yes. My own high school biology teacher did this for me. I was happy to have been able to find her and tell her this, just a few weeks ago — 45 years after the fact! Sometimes teachers don’t understand just how deeply they can affect the mental health of their students, and we need to explicitly acknowledge that that their kindnesses can help students enormously to change in positive ways. Of course, the reverse is true as well. Nina said this earlier: It’s is a simple conclusion from science, resilience rests on relationships. If you’re unhappy in your closest relationships, everything can be thwarted. If a child starts feeling secure, it can make the difference for their success.

Often teachers lose perspective on that element of reflection on their own well-being and practice, though we have students do it. This is often an element of teacher-research and teacher-training programs, but it is the first thing to go once teachers are working full-time.

SL: Teaching is demanding! These folks have to be attending to children’s mental health even as they are trying to teach them educational materials. To maintain community well-being, we need to look “upstream” at who’s running the ship, and in the classroom, that is the teacher. Everything’s affected if they’re doing well, or doing poorly. So you, as a teacher, are the upstream influence. Your wellbeing matters — of course your knowledge and skills do too, but to maximize them, we have to be sure you feel good as a human being. This is the big piece missing in our conversation as educators: where’s the attention to the wellbeing of those thousands of adults who are expected not just to teach children but to support their mental health through challenging times? As a society, we have to reflect upon that.

There can be two visions of what teachers, especially in the pandemic: on the one hand, teachers can be seen as heroes, expected to single-handedly raise children and teach them the ways of the world; on the other hand, they can be told to stay quiet, “just do their jobs,” and strictly transmit knowledge. These two visions can often coexist in the same conversation about teachers.

SL: I worry about how much teachers are taken for granted. Some time ago, I was talking to a Head of School in Rhode Island about the fact that teachers there were still not eligible for vaccination. The sentiment at the school was: thanks for the words and for calling teachers “heroes,” but we’d rather get real care for teachers. Apart from leaders in K-12 schools, people like us — who do research with schools — have the responsibility to be advocates for teachers. Researchers need to name the challenges that students are facing and to demand acknowledgment of how much teachers take on in trying to provide relief for them.

What are successful ways that schools and teachers have responded to the findings from a school survey?

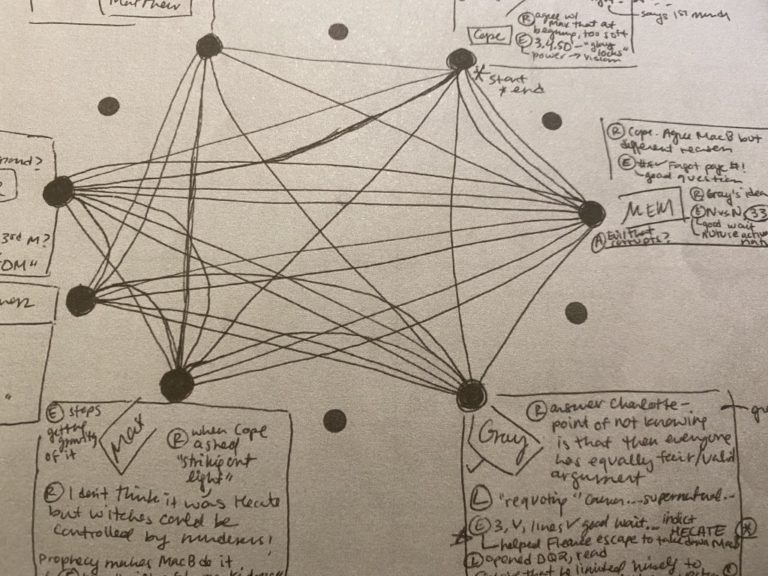

NK: One example — this is from back in in-person times, but the same story carries through. There was one school where issues around fairness came up frequently and was the variable most tied to mental health struggles. Suniya had gone on campus and done focus groups with students and talked a bit more about why fairness had come up, and it uncovered that there were traditions isolating students unintentionally. Traditions like a charity fundraiser, where students who raised enough money didn’t have to wear uniforms for a week, which separated students with family/family friends who could pay the money and gave them a distinct privilege. Things like that are present at any school, and sometimes these traditions are entrenched in the school’s culture and we don’t always think about their effects. A common example is that many schools have days where you get into college, and you wear your schools’ sweater, but the kids who aren’t going to college or didn’t get what they wanted in college admissions, feel isolated and embarrassed. Identifying these traditions, and talking about whether they do reflect the school values or not, has been really important in fostering belonging.

SL: We have several leaders in education who have shared how they have used survey data to benefit their communities. Quinton Walker of the University School of Nashville has a piece coming out with us soon in the NAIS magazine, describing initiatives set in motion because of survey findings. For example, they’re starting more peer support groups at USN and more time for advisory. Quinton also talks about what it looks like when you show faculty both the numbers and the words of students. It’s certainly useful to show where students stand in relation to national norms, but the students’ voices are powerful. Sometimes, in open-ended responses. they’re just asking: “Can you please, please, just give me a break?” With these words, the faculty can hear what’s in the children’s hearts; that’s a much more powerful way to motivate change than just numbers relative to national averages. Quinton has described many specific ways in which the data helped give focus on what’s most important to address, the rationale for this, and suggestions for HOW to make strategic changes.

From Bari Weiss’s recent article to the article on independent schools in The Atlantic last week, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Justice work in schools has been seen and criticized from every angle lately. Do you think that there’s hope to make meaningful positive change through DEI&J work? What works, and what do we need to do more of?

NK: The thing we’ve seen at a lot of schools that’s helpful is having information and data around a lot of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion issues. There’s work to be done in any institution around them. A lot of schools have been scrambling to try to get something done. In any given school community, there loud voices on all sides of any given issue, but it’s important to hear from everybody about the issues and how they’re feeling. Having thorough data can help to make actionable, responsive change to make sure people feel that they have a positive experience at school and in the workplace.

SL: There is no question that we should pay attention to diversity, but as Nina’s suggesting, you need thorough assessments to truly understand where the pressure points are. For example, within DEI&J issues, there are tacit assumptions about which groups are most at risk. Our data show that it’s not always what you’d expect. Multiracial kids, Asian students, or Hispanic kids might be the most vulnerable in a particular school. Sometimes it is white kids who say that they feel discriminated against. So our approach is always to go back and ask all involved, and not just assume or take anecdotal evidence from a few parents or kids. We need to understand everybody’s perspectives as we make decisions, and to understand not just how they feel, but also what the issues are and what the source is. For example, are there feelings of discrimination based on gender and sexuality? Where is this discrimination coming from — peers? Teachers? Parents? You need much more insight here. Like a doctor thoroughly examines a patient in so many areas, schools need to look thoroughly at what’s happening, and what most need attention, before they “prescribe the medications”.

The way we at AC address this is by doing multiple regressions to understand which aspects of school climate are most strongly linked with mental health. Almost always, social comparison and aspects of bullying come up; sometimes, the DEI variables are just as strong. All of this information is relevant in deciding action steps in a given school. There are fifteen things that are influential; maybe some issues around equity are shown to be important, but maybe they do not; you won’t know until you look at the data.

What is one prediction you have for the future of education?

SL: I think that schools and universities will have to grapple more closely with the issue of the whole child and what the kids are getting from the experience, overall. Parents will be asking more, what are we paying for? Is it “worth it” to send my child to private school? People are going to be forced to look more closely at mental health. So this is really not my prediction, but rather, it’s my hope – that there’ll be closer attention not just to rankings based on test scores but also on student wellbeing at a school. This is critical for the next generation.

NK: My hope would be that mental health is really integral in every school, foundational to every student’s experience. Like we’ve been saying, if students can’t do well, they can’t learn. We hope that more schools will incorporate health and wellbeing into their curricula.

SL: A wellbeing index — we’d like to see this on schools’ “report cards”, along with all the scores on academic successes!”

Authentic Connections’ research, including talks and white papers, are available via the Authentic Connections website.