Why Teachers Deserve Instructional Coaches: 5 Questions with Emily Gromoll

Teachers don’t always get the feedback they want and need. At R.E.A.L.®, we’re trying to change that with our program that offers on-demand instructional coaching for the educators within our network.

We sat down with R.E.A.L.® Director of Program Emily Gromoll to chat about feedback: what it typically looks like for teachers, what it would look like in an ideal world, and how R.E.A.L.® can help get closer to that ideal.

1. When it comes to feedback, what’s the typical experience for teachers?

One thing I realized when I first started teaching was how hard it can be to actually collaborate with other teachers in a way that feels substantial. As a teacher, you may only have an hour outside of teaching and coaching responsibilities – two if you’re lucky – and usually you need to fit in lesson prep, grading, or even conferences with students during that time. In my first few years of teaching, I was observed only a handful of times, and those observations were really just checking to make sure I had the basics covered: How was my classroom management? How were things going with my lesson plans? I felt like I was always grasping for more insights and advice on things like instructional structures, how to plan and align my curriculum, how to better assess student learning, etc.

2. Why is feedback so important for teachers?

We all know that our brains learn through reflection and feedback. And although many of us may go through a certification program or earn a Masters’ degree before we enter the classroom, the real learning happens on the ground – when you’re actually in front of students.

But we need time and space to take advantage of that learning process and be able to reflect on how things are going as they are going. It’s also hard to do that on your own. You’re only able to process through your own lens. When a colleague can sit in your classroom, add another set of eyes, ask questions that get you thinking differently, and share how they see the students learning the content or skills that you wanted them to learn, you can see much more than you’d be able to on your own.

We [teachers] need time and space to take advantage of [the] learning process and be able to reflect on how things are going as they’re going. It’s hard to do that on your own.

Emily Gromoll

3. Thinking about your experience working with teachers across classrooms: what has effective feedback looked like?

When I was working with my very talented and capable history department colleagues, whom I was eager to learn from, we would only have an hour of planning time together each week. That was just not enough time. In that one meeting, we would need to talk about book orders, upcoming events, teacher placements, etc., and then we’d have about 20 minutes left to get to the really substantial things like how to align to standards, how to sequence writing skills, and how to lead better discussions. Reflecting and planning together was very piecemeal and sporadic.

When I left the classroom, I started working for an organization that focused on supporting teachers with the process of instructional design and change. That experience completely changed my perception of what was possible. The way we worked with schools felt kind of like a think tank for teachers. As a facilitator/coach, I’d work with teams of teachers to identify existing problems they were experiencing, explore the root causes, set measurable student learning goals, then design instructional techniques and assessment tools to meet those goals and gauge progress along the way.

There were two aspects of that work that ultimately made the biggest difference when it came to feedback and reflection for teachers: First, setting up structures for non-judgmental observation. Sometimes we would structure the projects like a lesson study, with a bunch of teachers coming together to collectively design a lesson, then observe the students and take notes on how they did, and finally meet to talk about what we’d seen and what we’d change the next time. Having another set of eyes in a classroom to focus on how students are interacting with your content – especially when, as a teacher, you’re focused on content delivery – is huge. And it can be transformational for teachers: it shifts how you think about instruction. Suddenly the success of your lesson has less to do with how much content you got through, but rather how well the design of the lesson allowed you to assess student understanding of that content and give students targeted feedback.

Having another set of eyes in a classroom too focus on how students are interacting with your content…can be transformational for teachers.

EMILY GROMOLL

The second aspect that made a big difference was that as coaches, we were not just serving as thought-partners, but also as data crunchers and project managers. Teachers are creative people, so many incredible teachers are constantly coming up with great ideas for lessons, projects, assessments. But they are also BUSY people. I was the kind of teacher who had huge ideas all the time, and sometimes it was hard to sustain those ideas. I would try something out and wouldn’t know exactly how to collect the right data on it. When teachers have support to develop structures that help them make their ideas come to life and tweak them based on the feedback they get from students, it leads to better learning outcomes – for both them and their students.

When teachers have support to develop structures that help them make their ideas come to life and tweak them based on the feedback they get from students, it leads to better learning outcomes – for both them and their students.

Emily Gromoll

4. How does R.E.A.L.® shift feedback loops and give teachers a new lens through which to see their classes?

In R.E.A.L.® Discussions, teachers are not the facilitators of the discussion – the students are. There’s a bonus side effect of this shift when it comes to observation and reflection. If you’re teaching and trying to facilitate discussion, you can’t actually observe the class, because you’re responsible for navigating all the various elements involved in discussion. If you’ve done the work of helping your students figure out how to facilitate discussion on their own, though, you have an opportunity to think in a more targeted way about what it is you want to look for when the kids are talking and keep track of how they’re meeting those learning goals.

That can be really powerful. It’s even more powerful when you can have another teacher come into the classroom during a R.E.A.L.® Discussion and observe with you and talk about what you’ve both seen. When done well, this allows an entire departmental team to norm around these skills, create a shared language, and align and sequence curriculum.

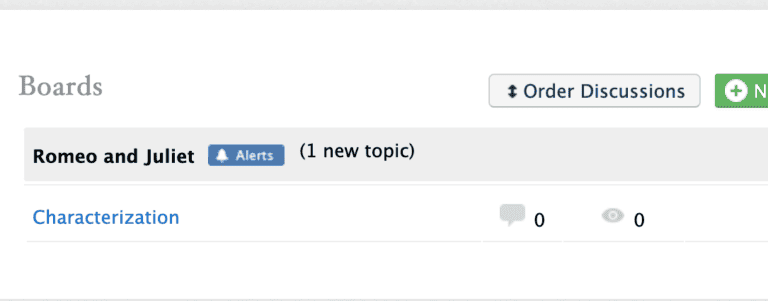

5. How does R.E.A.L.® provide feedback and coaching support to teachers?

There are a bunch of ways we offer feedback and coaching support to teachers – and we adapt that support to meet the varying needs of the teachers in our network. When working with a teacher (or teaching team), we often start by asking about their specific goals and what obstacles feel like they’re in the way of meeting those goals. Because so many artifacts come out of a R.E.A.L.® discussion, teachers have all sorts of data points at their disposal that can give them insights into both the obstacles and the bright spots. We can help them home in on the most relevant ones and use that analysis to fine-tune aspects of their discussion practice or troubleshoot what to do when students hit roadblocks.

We are lucky to have been able to see what this can look like across different grade levels, content areas, and kinds of schools. Consequently, we can also help teachers gauge how their students are performing relative to typical developmental patterns we see in how students learn these skills. Sometimes we offer validation to teachers worried that their experience is an anomaly – it can be reassuring to hear, “that is totally normal! We expect that reaction or outcome at this point in the year. We’ve seen that across multiple schools and grade levels!”

We can help teachers gauge how their students are performing relative to typical developmental patterns we see in how students learn these skills.

EMILY GROMOLL

For example: we’ve seen a pattern, especially with middle schoolers early in the year, where kids just share their excerpt and move on quickly in the first few discussions. Everyone takes turns sharing, but they don’t get deeper, and they’re a little afraid to disagree with each other. The first discussion often goes fast, everyone speaks, and it feels a little bit like a dud. Teachers come to us and ask how they can move past that. At this point, we have amassed a pretty substantial repertoire of strategies from working with so many teachers on how to best use those moments as learning opportunities for the students. We can share those and make suggestions across schools. And that kind of thing happens all the time. If a teacher comes to us and says, “I really need help writing a DQ around an ancient history article,” or a poem, or a novel, we can say, “that’s great – here’s what this teacher at this school did that was really effective.” Getting to be a connector across schools – sharing those brilliant, interesting exemplar practices teachers have come up with and then helping other teachers adapt them to fit the needs of their students – is one of the best parts of my job.

We count ourselves lucky, because we’re able to witness firsthand the creativity of the various teachers within this network, serve as a sounding board, and offer support. We believe that teachers deserve instructional coaches, and we’re happy to play that role.