The Case for Shifting Formality

Footnotes posts summarize the newest research related to student-led discussion. Think of it as teacher-approved SparkNotes (with better citations) for papers published by top schools of education, research-based websites, and think tanks. This week’s Footnotes post brings together two recent studies that (differently) challenge us to vary the formality levels of class discussion.

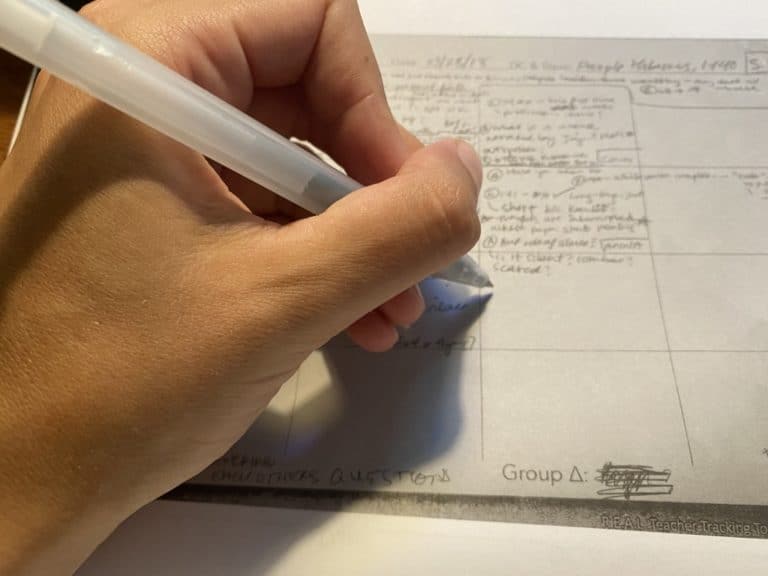

Mike Metz, “Amplifying Academic Talk: High-Quality Discussions in the Language of Comfort.“ Metz’s article, from the March 2020 issue of NCTE’s English Journal, asks teachers to actively dismantle the formalized speech patterns that often emerge in discussion-based classrooms. Using classrooms in San Francisco’s diverse East Bay for his research, Metz describes numerous circumstances in which students speaking using colloquial patterns make powerful critical observations in discussion. He also describes teacher moves that interrupt peers’ “giggling” over perceived informality and reinforce the value of students’ contributions regardless of the language used. Metz’s impressive literature review reiterates historical views that authentic student voice is empowering; his application of his research, which pushes teachers to “expand academic language” to dismantle perceived separations between the intellectual values of school and non-school worlds, reminds us that this work matters in the broader framing of education’s purpose in the world. Metz’s work reminds us of Zaretta Hammond’s Protocols for Equity and illustrates, through classroom examples, how culturally responsive teaching requires new, broader language for school discussion.

Orna Farrell and James Brunton, “A balancing act: a window into online engagement experiences.” Farrell and Brunton’s research in the Dublin City University online Humanities program focused on identifying key tactics for student engagement with and continuation in coursework. Because the online programs they studied often integrated older students, many of whom did not pursue higher education sooner because of the limits of social class, retention and engagement were specific concerns for them. Importantly, Farrell and Brunton’s work resisted some earlier conclusions that asynchronous discussion boards persuasively increased student engagement. Instead, they found that varying modes of interaction around course material — some involving teachers and some aside from teachers — helped students to learn effectively. For example, toggling between “the official institutional community,” “the student generated and student-led class community,” and “smaller cohorts of student-generated study groups” allowed for reassurance and connection in different ways. Students found that small sessions with tutors to guide through material in a less-formal setting offered an important variation in discussion. Particularly when teaching online or in a hybrid model, Farrell and Brunton’s work points out that the social connection of the in-person experience must be replicated somehow; chances to speak formally and informally about course content, goals, and questions enhances student engagement because it builds bonds on a variety of levels.