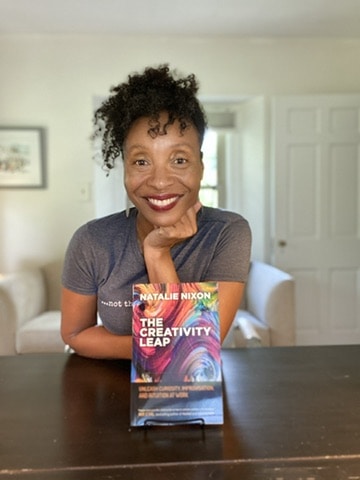

Office Hours with Natalie Nixon

The Office Hours series recruits experts from within the field of education and beyond to share their specific knowledge and perspective on a topic or a series of topics. This week, we spoke with Natalie Nixon, author of Amazon Bestselling The Creativity Leap: Unleash Curiosity, Improvisation, and Intuition at Work.

Katherine Burd (KB): In your book, you describe your time in an independent Quaker school and the role that that experience played in teaching you to ask better questions and drive you toward inquiry. I figured that that would be a great place to start. How did that school shape and influence your inquiry in your own life? What are some of the core concepts or structures that you remember helping that process?

Natalie Nixon (NN): I started at Germantown Friends School (GFS) in the 7th grade. The culture of learning was very different from where I’d come from. I started out in a crunchy-granola nursery school, and then I moved to an urban public school. In a school that was 98% Black, my mother had to fight to get me into advanced classes. There were only white kids in those classes, and I would complain to my mother because my friends weren’t there; she would reply that that was why I had to be there. My mother had to teach me my multiplication tables, how to tell time. If we (my sister and I) went to another public school in another county, in a suburb, my parents would have to pay tuition, but they did that for a better education. In the 4th grade, I was the first black child in the class at the suburban public school. Culturally, it was an ice bucket of water, though the academics came easily. But at GFS, I struggled academically for the first couple of years, because I was used to giving teachers what they asked for. Now, I was in a school where it was about asking a better question and being a provocateur. That seemed disrespectful to me at first, especially coming from my background, where, for example, you never called adults by their first names.

Walking down the hallway in 8th grade at GFS, I remember that it hit me that my friends back on the block and in public school were learning how to stay within the guardrails. In private prep school, I was expected to to blow the roof off. It was about disruption. I liked being in an environment where it was cool to be smart. What it equipped me with was that it helped me to hone my intellectual curiosity- a value which had started in my home. My mother was really the first intellectual I knew. She had won a full scholarship to Chatham College and transferred to UCLA and Temple …she had an insatiable curiosity. My father was curious about people, read four different newspapers every weekend, explored so much. My father had no patience for my complaints about GFS. He would tell us that he was sending us there so that we had options. At various times he held three different jobs to get us through school. He understood what I now know, which is that that education is a socialization device, and higher education is a way to access different social circles.

At this moment now, we’ve been hearing about how rich guys in Silicon Valley, their kids are circumventing college. In my opinion, part of the role of higher education is to gain access to a higher social sector. If, now, you can circumvent that with a cool job your parents could get you, you (i.e., some Silicon Valley parents) do that. Our country’s never been a meritocracy. There are so many kids who didn’t get the opportunities that I got. As you know, our public education system is designed around how big your house is, around zip codes. The education that I got was exhilarating, and also enlightening in a way that gave me pause. I’d been through the gamut of strata of educational environments, and it really struck me that now I had been admitted into a platform that would give me access in a way that I would otherwise not have.

KB: It’s striking me, and I think it’s a core question at REAL, that creative, student-led discussion as an educational practice is a privilege that comes along with small class sizes (generally, but not always, independent or tuitioned schools). And even within those spaces, especially in the current political environment, the power of freedom from constraint is still scary; students are wary of giving in to what you call, in the book, the “intuitive nudge.” Students fear an incomplete idea, and teachers fear that students won’t follow up their free thoughts with rigorous exploration. How do you recommend that leaders encourage those around them to act on their intuitions, and to follow up on it in a rigorous, developed manner?

NN: In all environments, people tend to do better when they’re seen and heard. That just gets diluted the larger an organization gets. The same goes with educational environments: when a student is seen and heard, they can’t fall through the cracks as easily, and hopefully the teachers are curious about their students, too. I taught at a school — De La Salle Academy in New York City — that didn’t have a lot of money (the students didn’t and the school didn’t). But the reason why it was such a rich, vibrant learning environment was because of size; that’s what’s key, beyond money or funding. Ten or twelve student classes led to a lot of engagement.

When it comes to intuition, we do have examples where we do relinquish to intuition: Athletics and the Arts. In both of those disciplines, there is an allowance for teaching the skill and the rigorous technique that’s needed for painting or singing or field hockey or track, as well as an expectation that, in the moment, students will be able to act on the scaffolding of the skill with intuitive, “flow”-like action. These activities are necessary for their carryover to intellect.

In the work environment, that use of intuition has to be modeled from leadership. For example, one of the people I interviewed in The Creativity Leap is Biplab Sarkar, who is the CEO of Vectorworks, a tech software company. I was nervous to talk to an engineer about intuition, but he acknowledged the role of intuition in decision making. He likes to couple it with data, but he totally embraces it. Organizations are organisms made up of humans who are perceptive about the ways that leaders model and tell stories. If you’re given permission, as a member of a staff, to follow a hunch, that’s an environment that’s encouraging you to experiment.

KB: As a teacher, there is an element of discomfort — and you mention discomfort in the book — but sometimes our students feel discomfort that they’re going to step into a role of leadership, especially in a class discussion. Some students are too eager to lead the jump, and an equal number feel deeply uncomfortable taking those public jumps. A lot of schools have devoted innovation spaces these days; how can we make those spaces effective and exciting, rather than fearful, for our students? How can teachers meaningfully develop their own practices, and how can they best model that for their students?

NN: Great teachers are really great learners. They have an insatiable curiosity of their own. We also know how many educators are overwhelmed and overstretched. It’s a similar situation in corporate environments: it’s not enough to have a dedicated space, but there has to also be incentive, time, internal review, and compensation if possible for creativity. An innovation tool isn’t setting people up for success if it’s just created and becomes “the place where people go to play with post-its.” It has to be taken seriously by leadership and given space and time.

I have 25 years of teaching experience in different environments, from middle/high school to higher ed. Teaching is one of the few professions where your work in the moment doesn’t happen in conjunction with your colleagues. At Thomas Jefferson University, I was part of a group of faculty trying to break down silos in higher ed, and we were team teaching. It was difficult! The cadence was different. The environment teachers work in, which is pretty independent, is a significant factor we have to consider if then we ask them to innovate in a collaborative way. There’s a science to teaming; it has to be intentional, and there have to be checkpoints and check-ins, and there has to be acknowledgement that it’s difficult. That’s why students hate group projects, right? For teachers to work well with innovation centers, and vice versa, there needs to be a culture shift in a school.

KB: I’m catching onto the idea that building structure into exploration, and toggling between different modes, is important for teachers while they teach just as it is for designers and leaders in any business. The WonderRigor system that you set up aligns clearly with the REAL framework that Liza (Garonzik) presents — the idea of “Relate, Excerpt, Ask, Listen.” As teachers adapt any of these frameworks, teachers often wonder: how can I build a structure that will ask students to move on the axes between Wonder and Rigor, or between Asking and Listening. What structures do you see leaders using well to help those they lead move between these poles? Or do you see that as more of an organic process?

NN: I think it comes down to intentionally allowing for the space and time for metacognitive work — giving people the time to think about the way they think. I don’t always mean that in a really structured way, with journal entries and other such assignments. I shifted the way I taught from a more “sage on the stage” and seminar style a while ago. When I launched the Strategic Design MBA program, we switched to a more studio-style class. 15-20% of the class is more content-based, and then the rest of the class time is students tinkering and seeking solutions together. That model allows for a lot of that metacognitive work to happen.

When I was learning how to sew, my mother would teach us something and then leave us to try it. I knew not to pester her with questions while she was busy. It was the process of me figuring out what didn’t work and trying again — that’s a metacognitive process that happens when we learn by doing. And again, that’s a matter of size and scale. You need space in order to do that exploration. We’re all smarter than we give ourselves and others credit for; we do just need to let each other be, let each other grow and explore. Wonder and awe need dedicated time just as much as, say, rigor; they’re all intermingled. In the midst of the rigor, you’ll find that spark of wonder, and vice versa.

KB: Metacognition and inquiry sounds like two critical pillars; yet I’ve found that there isn’t always a rigorous connection between the two in research yet.

NN: There are leaders who want to respond with certainty, and then there are leaders who say “Hmmm, I don’t know — let me take a pause and try to figure it out.” That’s an amazing model of the confluence of inquiry, intuition, and metacognition. That’s a great way to model it (metacognition and inquiry) for any kind of leader or teacher.

KB: Discussion as a discipline isn’t natural to all students, or even to the majority of students. To find buy-in, or make a classroom conversation a useful tool, you need metacognition, right?

NN: Discussion in the traditional model only hits one of the sensorial models of existence — the oral and the verbal — which doesn’t touch so many of the other areas by which we make meaning in the world. Sometimes we think about discussion as just having answers, especially in the adult world. But asking questions is also a really vital part of conversation. Especially in the workplace, we often prize solutions over the processes- but the process of getting to the solution is so valuable.

Thank you, Natalie, for sharing your wisdom and experience with us!