Office Hours: Interview with Meghan Cureton

In REAL Time is a blog focused on bringing together practitioners of student-centered discussion to challenge, encourage, and provide inspiration to develop that practice. We met with Meghan Cureton, founder of Cureton Consulting, to hear about how she leads teams of educators to make such interventions.

First, what brought you to the consulting work that you do now? What experiences led to this current role, and what values center your work?

I wish I could say divine intervention, but it wasn’t that simple. I wanted to spend more time with my family and model for my kids what it means to put others first, and that led me to take a new direction in my career. I’d been at Mount Vernon School (GA) for a long time, and my kids also attended and enjoyed the school, but my husband was commuting an hour and a half so that we could live close to my job. We found a house in a new neighborhood to ease his burden, and I was going to leave Mount Vernon, but I didn’t know what I was going to do. This was before Covid, and there wasn’t a structure in place for employees to work remotely. My school head still wanted to work with me, though, and proposed that I consult with the school to continue some of the innovation work I’d been doing. Since then, I launched my business full-time and now have some incredible partner schools I get to work to support.

I’m drawn to organizations and people that believe in a culture of learning. Within that, my specific work is driven by inclusion, creating a safe space for members of a learning community to take risks and share ideas. I enjoy helping schools create structures to feel like their voices are heard. The second principle is empowerment – I want to help schools build the processes to accomplish and sustain change without always relying on outside assistance. Part of what I do when I consult is model what it looks like to muddle through problems and create a set of processes and tools that leaders in schools can replicate in the future.

One of the features one notices about your work, even when scanning your website, is that each project seems to be framed around a question. How do you structure and approach innovation in school environments?

Most organizations and schools do a good job identifying the symptoms of a problem, but because of the pace and structure of life in those environments, they don’t often have the time to identify the root cause of those symptoms. When I’m approached by a client about a new project, I know I have to do a lot of digging to identify the root cause of that symptom. I want to get to know the people and organization through questions first. Then, I build a hunch around root causes and use design teams to test hypotheses. Most of the time, through that investigation, I end up giving language to something that everyone knows is there but that no one has named yet. In doing so, I’m able to give people a way to talk about a problem. After identifying that problem, we need to establish where the gap is between the problem and the experience of it (the symptoms). We launch some quick prototypes to see if we even really have the right problem; this step can feel exhausting, but it’s important, because acting on the wrong problem can lead the group in the wrong direction. You learn things in the process as you keep iterating; it’s messy. That’s where I come in as a facilitator. I set the roadmap and the guideposts to keep the process moving. People can move forward implementing, because I’ll create guideposts to make sure exhaustion doesn’t take over.

One thing I want to instill in organizations I work with is that you don’t need to wait for the whole thing to build out before launching an initiative. I’m there to push people out of the idea that you have to know everything that comes next. Part of the work we do isn’t just the specific work at hand, but also creating a way of working together so that next time you have to build a next step, you have the tools and mindsets to do it. I come in to model and facilitate in a replicable way, providing scaffolding and giving people a toolset to be freed up to immerse themselves in the work.

Teachers who use the technology of discussion already have many great tools in their hands. What does it look like to rethink or redesign existing pedagogical structures (vs. implementing completely new systems and approaches)?

I want to be careful with answering this. Some people believe that what makes a great discussion is the tools or the tech that can shake things up. Good discussion comes down, though, to how socially and psychologically safe people feel. Priya Parker’s The Art of Gathering is a big inspiration to me when I think about how we can accomplish this. How different would it feel if schools/teachers would use her framework as a tool to host discussion?

First: it would mean making every class discussion clear on its purpose. We think about “oh, the purpose of this class is to be English class,” but there needs to be a clear purpose for each specific gathering. You get to choose what that template looks like. The structures that go with it should fuel that purpose. The other result of applying Parker’s framework would be moving past this false assumption that if you’re doing a learner- or student-centered approach (I say learner because I don’t want to create a teacher/student separation), the teacher is doing her/his own thing. In Parker’s work, the teacher facilitates, but that facilitation doesn’t need to be prominent. This is one of my favorite quotes of hers: “gatherings crackle and flourish when real thought goes into them… when often-invisible structure is baked into them and the host has the generosity to try.” If a host goes in wanting their facilitation to not be as prominent as the voices of students, and curiosity, willingness, and generosity are part of that spirit, schools will be different.

How can teachers who have innovated in their practices use those individual experiences to enact broader pedagogical shifts in their schools? Conversely, how can schools empower innovative teachers to enact broader change?

I’m a big fan of leading from where you are. Civic movements and shifts often can and do happen with grassroots efforts. I’ve been thinking about concrete ideas. Don’t wait for the leadership to schedule a professional learning session. There’s this fear if it’s not on the agenda, you’re not allowed to do it, but teachers should feel comfortable to create their own experiences. The other concrete action that teachers can take is around gathering people and ideas regularly. Hang out; drink the coffee near your colleagues (when all that is safe again) and talk about what they’re doing and trying in their classes. Walk down the hall and see what others are doing in their classrooms. If you don’t have an open door policy at your school, then ask other teachers if you can observe them. You’d be surprised how quickly that kind of thing can take off. It can change a community of teachers into a community of learning.

I think there also needs to be some advice here for leaders trying to support this work at their schools. I’m in conversation a lot with school leaders who say that no one likes change at their schools; they feel as if they can’t make changes. I push back on that. Nobody likes change to happen to them. But if you create structures that inspire change and empower teachers to make change, they will. If/as teachers are doing this and you aren’t invited as a school leader, let that happen. Set up conditions for them to talk about what they’re learning and trying in the classroom. Then, find opportunities to celebrate teachers who are doing things.

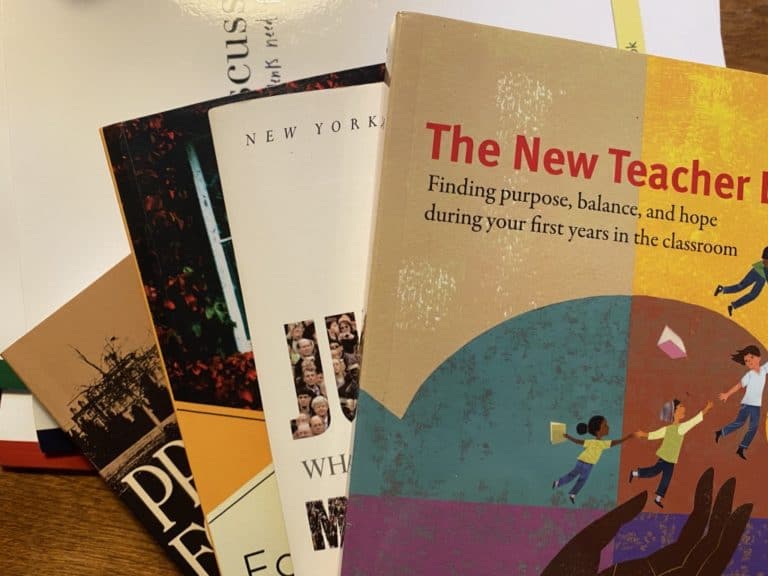

What are you reading lately that you would recommend to teachers?

One of the biggest ones for me is Caste, by Isabel Wilkerson. It’s really impacted me in a lot of ways that recent books haven’t much. I read it once on my own and once in a book club. I think it goes back to what I was talking about before about getting to root causes. That’s why I appreciate her work so much. She talks about root causes and structural issues that we’ve built on top of in this country. I’m interested in how we untangle that mess. Her work trickles into education because everything we do is also built atop this caste system. She talks about everything, and the way she describes the reinforcing of hierarchies within systems is both powerful and devastating at the same time.

Another book that’s come up with a lot of schools is Futurewise by David Perkins. It looks at different ways about “bucketing” curriculum. One thing I’m noticing is that the clients that are approaching me right now are saying there’s a massive shift in curriculum organization that’s not going away. How can we rethink those structures? What would it look like to structure courses, classes, and other programming in different ways?

What’s one prediction that you have for the future of education?

I think we are in a potential slingshot moment across the country. It’s more critical than ever to be intentional reflecting on this past year — schools should be asking their communities: what did we learn this past year? What should we STOP doing? What should we KEEP doing? What should we START doing? Now that we know what we know. S that will be the most successful will be the ones who privilege that conversation and see this next year as an opportunity. The schools who personalize their selection of pedagogical resources in new ways and take advantage of the tools they have at hand. Schools that are willing to adopt things like REAL, have 2-3 faculty members working from home and creating online classes, willing to collaborate with other schools and produce things together, not in isolation — schools willing to prototype new ways of serving their learners will be most successful.

Another thing is that it’ll be impossible to ignore the inequities that Covid has highlighted. I don’t think that conversation is going away anytime soon. Wilkerson’s work is extremely relevant when we approach this conversation and the actions it prompts for schools. We can do all the surface-level and day-to-day work, but if we don’t look at the inequitable practices and structures underlying that daily practice, we’ll get nowhere. That’s the conversation we’ll have as we move forward.