Office Hours: 30 Minutes with Alexis Wiggins

Alexis Wiggins has worked as a high-school English teacher, instructional coach, and consultant. Her book, The Best Class You Never Taught: How Spider Web Discussion Can Turn Students into Learning Leaders (ASCD), helps transform classrooms through collaborative inquiry. Alexis is currently the English Department Chair at The John Cooper School in The Woodlands, TX. You can contact her or sign up for her newsletter at www.ceelcenter.org.

First, tell me how you would describe your current professional title(s).

I’m an English teacher and department chair at the John Cooper School in The Woodlands, Texas. I also write and consult when I can. As a consultant, I work with schools to help them design better assessment practices, developing dynamic curriculum, using essential questions, and implementing effective student-led collaborative inquiry in all kinds of classrooms.

You’re most known for your Spider Web discussion practice. Can you tell us a little bit about how that tool developed and what you’re valuing about it most these days?

Working at The Masters School (in Dobbs Ferry, NY), which is a Harkness institution, shaped my practice and played a significant role in developing Spider Web Discussion. Long discussions about books were part of my own education; I didn’t experience a lot of lectures in high school, so discussion of a kind was a familiar teaching medium for me. I was in my 20s when I started teaching, and entering the classroom as a teacher forced me to reexamine assumptions that I had about discussion. First, I had to think about putting the onus and empowerment on students’ shoulders, empowering them to be ones who asked the great questions, rather than waiting for me to ultimately guide the discussion. I learned through Harkness that if you bite your tongue long enough, kids usually get where they need to go on their own. They also value where they land more, because rather than having it spoon fed to them, they found it for themselves. Like most Harkness schools, Masters implemented the Harkness pedagogy in all disciplines. But the English department had a collaborative model that was different from what I’d seen prior or since: the whole class would get the same discussion grade for each discussion. This practice took away the individual element and made the classroom a fully collaborative inquiry. That was very new and different for me as a young teacher.

For years prior to that, I felt like I had been rewarding bad behavior: volume, not necessarily depth of comments; interruption; not listening well; the students who engaged in these less productive ways ultimately earned higher grades. When I considered my values or goals for discussion, I realized that my goal wasn’t to have kids speak more, but to encourage them to ask questions, to reference the text often, to be unafraid to say they’ve rethought and want to follow up with a question. This model – which the English department at Masters had decided on before I got there – was the origin of Spider Web Discussion for me.

I ended up building avenues out from there that better supported the method in schools that weren’t Harkness. I couldn’t do that group grading in environments that weren’t designed for it, and I ultimately don’t think that it’s best practice.

Spider Web Discussion really empowers kids to do the deep digging and question asking themselves. A good teacher can use it to lay groundwork and protocol and give spaces for feedback and reflection while providing intellectual safety.

What do you value about Spider Web Discussion most these days?

We’ve never been so divided as a country. The ability to listen to each other in all types of perspectives or interpretations is critical, as we all know. Whatever we’re talking about, we have to be able to come together and listen and reason and ask questions that are challenging. At the beginning of the year, I decided to implement a class charter activity that I learned about through my school’s partnership with Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence. It’s an activity where kids write about how they want to feel in class. My students listed these words: comfortable, encouraged, respected, challenged, listened to, free to make mistakes, passionate, relaxed, happy, creative. That kind of answers the question, for me. If students want to feel those things, something like REAL or Spider Web Discussion provides daily opportunities to foster that kind of classroom.

What questions are on your mind as you design for and in classrooms this school year? What do you think teachers should be paying attention to as they foster classroom discussions, perhaps especially if they’re in a school in which student-centered discussions aren’t common practice?

One of the things that has helped our school and other schools I know develop a more cohesive model, even when they aren’t Harkness schools, are essential questions. Having essential questions that frame a course or even a department can be really unifying, providing a wonderful starting point for any kind of teacher. We started this year with our first Spider Web Discussion in several course with essential questions, such as:

- “Are people inherently good or evil?”

- “What’s true? What isn’t? How do we know?”

- “Is language a weapon or a tool?”

We introduce the questions to frame the year, and we have them write a benchmark essay that responds to one question using their summer reading as evidence. Those questions are the anchors for the year, and we post them on the walls of the classrooms; each course has between 5-8 questions. Not all of the questions come up in every unit; they’re an anchor again and again, both for content (like understanding Orwell’s 1984) and assessments (writing an exam on a single essential question, using the term’s content as possible evidence). Essential questions are a game changer for anyone who’s looking for something to center and motivate class discussions.

Can you assess discussion? If so, how?

It depends on every teacher and every context. At a Harkness school, it was appropriate and expected to make discussion performance part of a student’s grade. Everybody bought in. Other schools might be standards-based, or have policies that no group grade could ever count. I would also argue that if we want to truly teach, encourage, and develop students who collaborate well, then we need to assess their collaboration. That assessment of collaboration is something I’ve rarely ever seen. How well are we assessing the act of collaboration? Getting specific targeted feedback on how well you (as a student) collaborate is important if you want to grow as a leader and team player, both in school and career.

In the past five to seven years, as my teaching has shifted and since the standards-based movement has gained ground, I mostly assess discussions as group grades and treat it as a formative assessment that counts as zero percent of the overall average. I think this is more accurate in terms of individual student assessment but it still keeps the focus on the group’s collective inquiry through a “symbolic” grade. People always ask if students will still take discussions seriously without the individual grades, but for the past decade, I have seen no difference in quality between discussions that “count” and those that are formative. The rubric works either way in my experience.

What about providing individual feedback to assess individual skill development?

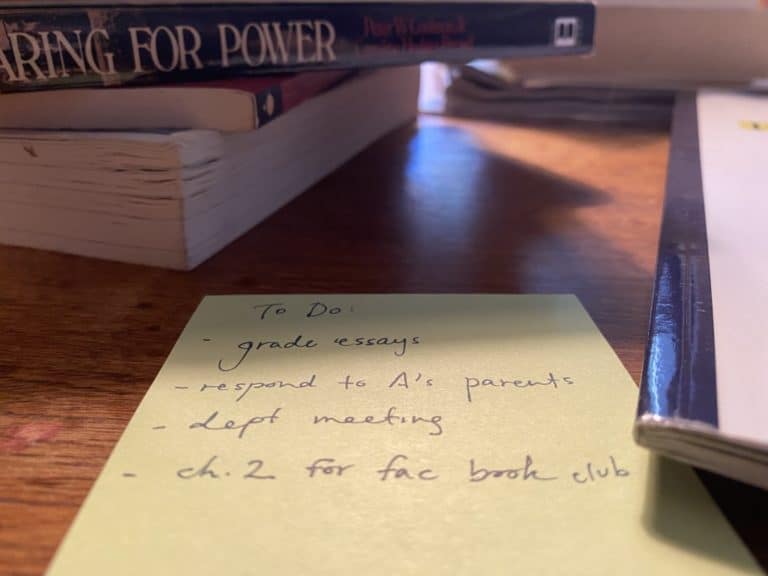

I default to not doing that as much, though I love the way that REAL offers that individual feedback. A lot of our faculty has done the training [for REAL], and we’re implementing it in seventh grade. I don’t generally give a lot of individualized feedback, though we always do a lot of debriefing together, and I love to shout out a lot of specific students. The potential is there and should be encouraged for anybody who has the time. I think that decisions about how and when to give individual feedback should be site-specific. It’s worked so well for me to focus on the collaborative aspects of discussion, but it can be different in other places.

What’s one prediction you have for the future of education?

I predict that it’ll be one of the most attractive fields to work in in the next generation. I think that there’s less job security in so many fields that are traditionally seen as attractive to students. I think that we’ve also seen the importance of in-person teaching. We’ve all lived it. Five to ten years ago, everyone was talking about MOOCs [Massive Open Online Courses] taking over the world, but it seems we’ve really decided that there’s something really important about being in person.

Every week, I give my students my “Advice of the Week.” One piece of advice I give each year is to “become a teacher. No, seriously.” I’ve never been out of work, I’ve been able to teach around the world, I am lucky enough to have my own children at the school my husband and I teach at. It has brought me so much personal joy to teach the subject I love to great kids for the past two decades. It’s hard work, but it’s meaningful work that matters. I wish more young graduates saw the field this way, and I wish there were more funding for schools and educators to ensure equity across all kinds of schools.

I know, from your work in developing CEEL (Cohort of Educators for Essential Learning) that you’re interested in creating communities of teachers. How can we, as teachers, support, comfort, challenge one another as teachers of discussion?

I would love to know the answer to that question. Do you have it? There are so many great places to create community, so many opportunities, but I also think I’m still figuring it out. Even just Twitter has been a wonderful space for me; I follow a few journalists, but then everyone else I follow is an educator. Twitter is where I go to see what’s new and different – I look at #aplitchat and other spaces that are often active. I especially think that new teachers should enroll and engage on Twitter. It can be a community that still has very low stakes; you don’t have to engage, you can just observe. If you don’t want to give time and energy to initiatives, it still gives you something.

It’s really hard to actually build and find professional communities and teaching beyond your work. Personally, I tried to organize a conference of teachers, and I found it hard. It didn’t really work out. Mostly I was creating it because I wanted to benefit from it, but the logistics side of organizing it was beyond what I could do as a teacher. In the absence of that, I’ve tried to stick to the conferences and spaces that I’ve found to be amazing when I attend them.

I joined the New York Times Teaching Project this past June. They chose forty educators, and we spent a year together in monthly Zooms. You also have four days in person at the Times, though ours was virtual this year because of the pandemic. The summer week-long institute was amazing, even online. We each create a curriculum project using the Times as a resource. It was by far the best professional development I’ve ever done in my life. It’s so rare to attend professional development where everybody who’s attending 100% wants to be there. It’s riveting, because during every session you have, you’re learning and growing and getting feedback and taking notes. It’s so exciting to share spaces with like-minded, energetic people; it doesn’t happen for me in every workshop and conference I attend. More specialized, area-specific settings definitely help to create that alchemy.

It’s important to find the spaces that speak to your specific needs. That’s the most fulfilling. When you find the right people to follow on Twitter, the right network, the right groups, then you can narrow down and find the people you want to work with to learn and grow.