The “Asking” Skill: A Challenge and Opportunity for Students and Adults

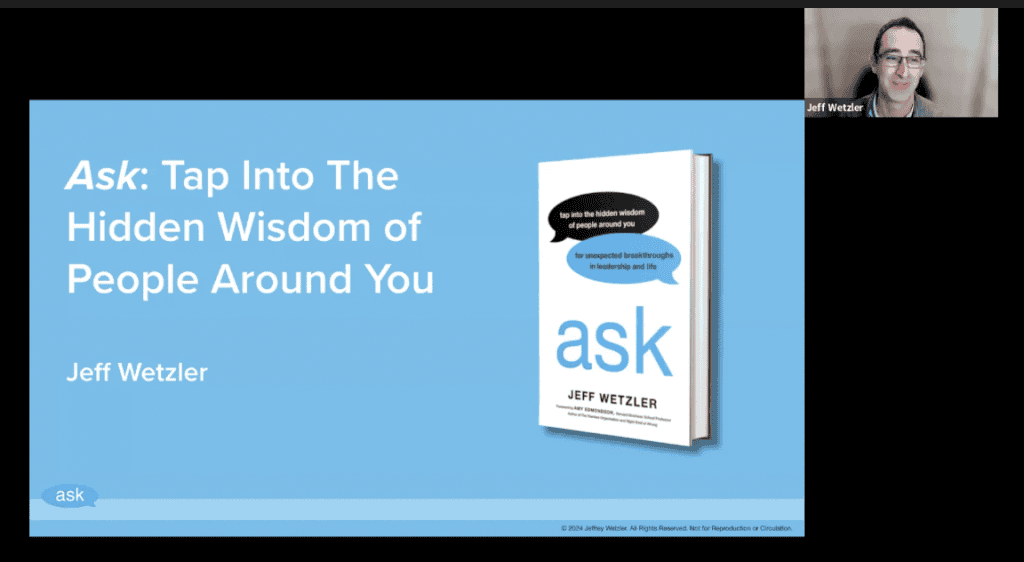

Last week, we were thrilled to welcome friend-of-R.E.A.L.® Jeff Wetzler to give a keynote presentation to our intrepid R.E.A.L.® educators. Jeff, the former Chief Learning Officer of Teach for America, is the co-founder of Transcend, an organization that strives to support school communities as they create extraordinary, equitable learning environments, and the author of Ask: Tap into the Hidden Wisdom of People Around You for Unexpected Breakthroughs in Leadership and Life.

Like us, Jeff is, in his words, “obsessed” with conversation – and, namely, with all of the things that aren’t said during discourse. His book helps readers grapple with a fundamental problem: the fact that we’re all constantly surrounded by people – students, teachers, coworkers, bosses, family, friends – and, for the most part, we have no idea what they’re actually thinking and feeling.

Asking to Learn

As Jeff said during his keynote, “it turns out there’s only one thing that reliably allows us to know what other people around us think, feel, and know – and that’s to ask them.” Asking other people point-blank what they’re really thinking and how they’re really feeling, though, is easier said than done – and barriers to doing so are erected from the earliest days of childhood. Jeff told us – and parents and teachers can likely confirm – that kids are naturally curious. By the time they reach age four, they’re asking an average of 400 questions per day.

It turns out there’s only one thing that reliably allows us to know what other people around us think, feel, and know — and that’s to ask them.

Jeff Wetzler

That number diminishes as kids receive subtle cues – from their parents, from their teachers, from the way instruction happens in their schools – that asking so many questions is annoying, unnecessary, or unproductive. “Many schools reward kids more for giving the right answer than for coming up with interesting questions,” Jeff notes. “All of that combines to suppress question asking among kids.”

At R.E.A.L.®, we see firsthand the ramifications of devaluing questioning. Asking questions is a fundamental component of a good discussion – indeed, it’s a foundational element in our program – and it’s a skill many kids simply do not have. What’s more, our data show that learning to ask high-quality, constructive questions is a skill that takes time to develop, even after starting our program.

Like Jeff, we champion the earliest possible instruction of the “Ask” skill. We also know this is a skill that eludes many adults – but it’s never too late to learn.

Jeff Wetzler’s “Ask” Framework

Jeff has created a framework that helps people of all ages tap into the unspoken collective genius that surrounds us everyday. This framework is made up of a handful of science-based, practice-tested elements, including choosing curiosity, making conversations safe, and – our favorite at R.E.A.L.® – reflecting and reconnecting (among others).

During his keynote, Jeff focused on one particular element – “Listen to Learn” – and discussed how to put the framework in action through a hypothetical conversation between an eager, ambitious new Head of School who’s unrolling a new academic program and a long-tenured, well-liked Academic Dean. In this scenario, the Dean likes the Head and respects her vision and commitment to innovative pedagogy, but worries that she is pushing for big changes without really understanding the nuances of their particular school.

We’d wager that many R.E.A.L.® practitioners have been part of these types of conversations, which are strained by silent tension, complicated by good intentions, and prolonged by everything that goes unsaid. The educators who joined our session unpacked the various emotions each party in the conversation might be having, dove into the many layers of meaning within their sentences, and posited about the repercussions of, at best, a missed opportunity to learn from one another and, at worst, a true misunderstanding between the Head and the Dean.

The only way to elucidate this complex web of context and emotion would be for the Head and the Dean to ask each other more explicit questions about their thoughts and feelings. Asking the right questions, though, is yet another challenge.

Putting the Framework in Practice with Quality Questions

Jeff distinguishes between “quality questions,” or those questions that foster learning, and “crummy questions,” or those questions that block learning. Whereas a “crummy question” might be clumsy, close-ended or rhetorical, manipulative, or even combative, a quality question signals true curiosity and invites honesty.

A quality question signals true curiosity and invites honesty

Jeff Wetzler

In the hypothetical conversation we enacted and analyzed during Jeff’s keynote, attending R.E.A.L. ® practitioners brainstormed the stakes in not reaching true learning and understanding for our imagined Head and Dean. “The Head risks losing an essential ally,” said one educator. “He’ll give her a few chances, but if she’s not interested in what he has to say – or appears that way – he’ll lose confidence.”

Others noted that there could be real insight and opportunity in what the Dean has left unsaid, and in the open discussion that hasn’t happened. Someone noted a dire potential consequence of misalignment: if parents lose faith in the educational program, enrollment could suffer. Someone else summed it up concisely and powerfully: trust is at stake.

So what would quality questioning look like from the Head and the Dean, respectively? Our educators agreed that if the Head asked questions like “How has change been received in the community in the past?” or “What are some concerns you’re hearing? Do these go beyond normal reactions to change?”, that could open the door to a more productive dialogue.

Likewise, quality questions from the Dean might sound like: “How might my experience at the school be helpful to you as we move forward?” or “I appreciate your efforts to improve the school. How can I help you understand the nuances that are involved?”

It’s in discarding the crummy questions and embracing the quality ones that true learning and, thus, understanding can begin to occur. This is as true for the hypothetical Head and Dean as it is for our own conversations with colleagues and friends, and as it is for our students’ class discussions.

We’re so grateful to Jeff for his pioneering work in examining and elucidating what it takes to ask good questions – and we’re committed to practicing the skill, whether in class, in the office, or around the dinner table.

Thank you, Jeff, for sharing your wisdom!