Understanding the “Organ of Learning” : Brain Science with Glenn Whitman

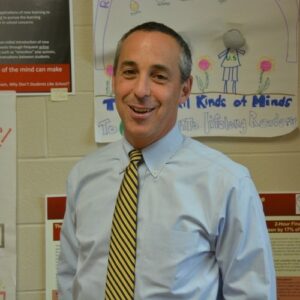

Glenn Whitman is the Executive Director of the Center for Transformative Teaching and Learning at St. Andrew’s Episocpal School, where he also teaches history. The CTTL’s mission is “to elevate teacher effectiveness, student achievement, and the whole child’s school experience using the most promising research and strategies in Mind, Brain, and Education Science.” What follows is a conversation between Glenn and R.E.A.L.® founder Liza Garonzik, which has been lightly edited for clarity.

What is your “why?” What is your North Star, and why does your work matter?

I’ve been in education for 31 years, and I’ve been a history teacher for every one of those years. I will never give that up. My “why” has always been to be the most impactful teacher for the kids who are in front of me, every class period.

I came out of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania with a major in History and then got a master’s in history, but I really didn’t have any understanding of pedagogy or how to teach. I used to think my education philosophy was: I teach, they learn, and I love my kids. That was it.

My “why” has grown as my work has extended outside of the everyday classroom. I’ve written a book called Neuroteach with a colleague on the science of how the brain learns and its connection to the classroom. I think my extended “why” is that I want to leave this profession and craft having impacted as large an audience – including students, teachers, parents, school communities, whether they be private, public, independent or international – as possible.

Hopefully, I have contributed with our CTTL team to elevating teacher understanding of the science of how the brain learns around the world.

Having looked at your work and having operationalized so many of your concepts in the design of R.E.A.L.® is how tactical it is. You can tell that you’re a science nerd with the research element, but fundamentally, you can also tell that you’re a teacher.

To that end, do you have a few top tips for a teacher who says: okay, I want to know more about how the kids in my classroom’s brains are firing?

The first tip is about mindset. I think too many teachers feel like they have to be the loudest voice in the room, and that there are certain things that we’ve latched onto as examples of good teaching. But teaching is a growth industry – for the teacher and the students. I’d encourage teachers to change a little of our thinking about what it means to be a good teacher.

In terms of tips regarding the connection between teaching and brain science, when the CTTL travels around the world and presents to individual teachers, schools, and school districts, we always start with a few things. First, we try to create a collective vocabulary to make talking about teaching learning at a school more efficient and coherent. Common vocabulary helps.

Also, if there’s one concept from neuroscience that’s most applicable to the classroom, it is neuroplasticity. If you don’t believe in this idea that the brain can change and grow at any age, then I’m not too sure this is the right career for you. We’ve got to believe all kids can change and get better between the start of a school year and the end of the school year. We believe strongly that this concept of neuroplasticity should be foundational to every teacher training program.

We also want a second thing: a focus on the connection between emotion and cognition. As a young teacher, I wasn’t really aware enough that kids bring their emotions and identity to class every day. That has a huge impact on where the learning is going to happen for them and their peers. As teachers, we need to think about both emotion and cognition. This is why that concept of belonging – a student’s social and emotional belonging as well as their academic belonging – fits really well into each of our classes.

And finally, thinking about the cognitive load of being a student and the schools we’ve designed and created for kids is some of the best research out there for us to consider. We know there’s a lot of extraneous load on a student’s active working memory that gets in the way of them doing the learning and working with the concepts that we want them to.

So in sum: I would say we need to alter our mindset of what a great teacher is and does in the classroom. We need to consider that neuroplasticity is a non-negotiable element of neuroscience. We all should know that emotion and cognition really go hand-in-hand in excellent learning experiences. And that cognitive load theory, as Dylan Wiliam has often said, might be the most important thing that all educators should know as well.

Can you talk a little bit more about how using brain-friendly practices can help every child feel as if they belong in a class?

Yes, and I think it ties in very well with your work at R.E.A.L.® To be honest with you, I knew nothing about belonging for a long time. We got to it through our understanding of growth mindset.

A lot of people have heard of growth mindset through the work of Carol Dweck and Angwela Duckworth. How we got to belonging was through what was previously called the Mindset Scholars Network, which then became the Student Learning Experience Network. Through research, we learned that there are actually three mindsets.

There is the growth mindset. There is a mindset called belonging, which is very well-researched from the likes of David Yeager and so many others. And then there’s also a purpose and relevance mindset.

We got to thinking: if a student doesn’t feel like they belong at a school, forget having a growth mindset – nothing is going to happen. So we started thinking about how to create academic and social belonging.

Some things that I’ve done are simple. For example: I want every one of my students to hear their name – not through attendance – within the first seven to eight minutes of my class. If a student hears their name, that is signaling something to them: this person actually knows me and cares about me.

This is where the work R.E.A.L. ® is doing in getting kids to be good questioners can really help. Making sure we’re hearing all kids’ questions is critically important. When I ask a question, I want everyone to respond. But if I put an idea on the board, I also in reverse want everyone to write a question about it. That creates belonging – if every kid knows they’re going to be able to ask a question and answer a question in a school class period. That, to me, is belonging.

The problem with belonging at least in the U.S. is that there’s a lot of talk about diversity, equity, and belonging, and it’s become part, unfortunately, of these cultural wars in this country, when in fact a sense of belonging is just a human need. Every student – and every teacher, too – needs to feel like they belong in their schools.

I absolutely agree. At R.E.A.L. ®, the way we define belonging is we want every child to feel seen, heard, and comfortable being challenged.

I love your use of the word challenge. I see this a lot: we need to have a high bar for every single student while also understanding that not every student starts at the same place. I’m a history teacher. I know not everyone is going to come into my class with the same prior content knowledge and skills. But my bar for everyone is equally high.

And that’s belonging. When you change your bar, you are deskilling kids for their readiness.

Absolutely. In your movement from teacher to researcher to author to director of a global education nonprofit, what’s one thing you’ve learned about leadership and your vision for schools? Having seen them from all different sides, what do you hope that schools can be?

It’s a great question. I’ve learned a lot. We launched the center in 2011. When we started the work, and even now, we were and are continually amazed by how few educators, teachers, school leaders, and certainly policymakers have an accurate foundational understanding of the science of how the brain learns.

It’s sort of ironic – the brain is the organ of learning. You would think that understanding how it works would be non-negotiable. I’ve often joked that if I went to my cardiologist and they said, “Glenn, I love your heart. I care deeply about your heart.” And I said, “Doc, have you ever studied the heart?” And if they said no, I would get the heck out of there!

That’s what we’re doing with kids. Teachers generally love teaching, and they hopefully love their kids. For many of them, though, it wasn’t required in their teacher training programs to prep programs to understand foundational science of teaching learning. That still surprises us now.

On the other side, we’re also surprised by how many great books have been written in the space, and how it’s possible to have very easy wins in your pedagogical practice, curriculum design, and connection with kids.

We’re learning that there is still a true opportunity to close or elevate learning gaps, achievement gaps, and school experience gaps. There are opportunities to use what we currently know about the science of how the brain learns. And we want to be one of those organizations leveraging that research and those strategies to support as many kids around the world as possible, as many students, schools, districts, and parents, who are critically important partners in this work.

I appreciate your optimism on how teachable it is. The thing that stands out to me is the importance of this work in a world where tech is evolving as quickly as it is, and kids’ brains are developing differently in response to technology exposure. It feels even more critical to have some baseline understanding of how the human brain works. As we watch it change in the decades to come, we need teachers who are able to respond accordingly.

I’m excited about the possibilities with technology. It’s not going away. But you still need to know foundational principles in science of teaching learning to leverage the technology that’s sitting there for us to leverage.

Absolutely. Ok, and now some rapid-fire questions. First: what’s your favorite school supply?

A really good lunchbox.

Who was your favorite teacher growing up?

Professor John Osborne at Dickinson College, who was not only my history teacher but also the head men’s soccer coach.

What’s your favorite unit to teach, and why?

My favorite project is our big oral history project. I love the Salem Witchcraft Trials, because it allows us to talk about three periods in history at the same time: the 1690s, the 1950s, and the witch hunts that seemingly are part of 21st century America.

Excellent. Thank you for your time, Glenn!