A Researcher’s Perspective: 5 Takeaways from Watching R.E.A.L.® Discussion in Action

by Harriet Piercy

Harriet Piercy has taught English at London secondary schools since 2015 and held a number of roles as a curriculum leader. She is currently joint head of the English faculty at Haggerston School in Hackney. She was recently a Fulbright Distinguished Awards in Teaching scholar at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, undertaking research in oracy. During this period she worked at a metro public school in Nashville, visited and observed at a range of other schools across Tennessee, and interviewed educators and specialists in the field of oracy. Harriet holds a First Class degree in English literature from Durham University and a PGCE from the Institute of Education, UCL.

As an English secondary school teacher in the UK, I’ve experienced the challenges involved in promoting a culture of speaking and listening in my classroom. In England, our National Curriculum outlines a requirement to create “spoken language” opportunities, which are similar to (albeit much less comprehensive than) those of the Common Core in the US.

In reality, however, many teachers and schools lack the time, expertise, and framework to foster these skills in their students. This means that the quality of discussion-based learning varies significantly between schools in the UK.

At the start of this academic year I participated in the Fulbright Distinguished Awards in Teaching programme, researching oracy at Vanderbilt University. As I navigated the American secondary school system, I discovered that the education landscape was even more diverse than the UK, and approaches to speaking and listening were just as varied. When I was introduced to R.E.A.L.® Discussion by American educators, it sounded like exactly the kind of practical, skill-based approach that I was hoping to encounter. R.E.A.L.® and its generous partner teachers gave me an incredible opportunity to visit three schools in Tennessee, which gave me first-hand insight into the way the R.E.A.L.® approach is developed with middle and high schoolers. After each visit, I came away brimming with inspiration for the kind of oracy strategy I wanted to implement in my own school context in the UK.

My first school visit was a masterclass from Sumner McCallie’s twelfth grade class at McCallie School on how to foster independent, student-led discussion. After introducing the topic of discussion, ‘What are the central elements of being human?’, the teacher handed over the reins to the students. At Girls Preparatory School (GPS), Ralph Covino harnessed the power of the R.E.A.L.® Discussion framework with his seventh grade class to get the students reflecting on and refining their excerpting skills. At Hutchison School in Memphis, Julie Reynolds modeled how to break down the elements of effective discussion with her fifth graders, who were in their second cycle of R.E.A.L.®. In each of these R.E.A.L.® classrooms, the students were supported by the routines so that they initiated, developed, and probed one another’s ideas using the key tenets of R.E.A.L.® – relating, excerpting, asking questions, and demonstrating their keen listening.

Why R.E.A.L.®? Here are my five takeaways:

1. R.E.A.L.® for rigor (why the ‘prescriptive parts’ of R.E.A.L.® work)

By giving students a shared language and framework to participate in discussion, the how of speaking becomes increasingly automatic, which frees students to think deeply about what they want to say.

I observed the rigor of the R.E.A.L.®framework in the way it prompted the GPS students to relate their reading of Confucius to personal and world contexts; in how the McCallie students fluently excerpted from a range of sources and synthesized those references into their discussion; and when the Hutchison fifth graders identified specific instances from the short story Code Breaker to illustrate their ideas about the heroism of the Navajo marines in World War II. This kind of ‘accountable talk’ is exactly what leading researchers like Alex Quigley from the UK’s Education Endowment Foundation have identified as the best discussion framework, as it directs students to substantiate their views across a range of subjects.

2. R.E.A.L.® for metacognition

The use of group reflection in all of the classrooms I observed demonstrated high levels of metacognition. With different levels of support from the teacher as appropriate, students appraised both the quality of their own participation, and the effectiveness of the group’s cooperation across the discussion: at Hutchison, the students began with a clear set of intentions for the kind of discussion they were aiming for and were guided by Julie Reynolds to share precise feedback on classmates’ contributions; the twelfth-graders at McCallie, who’d had much more practice in the R.E.A.L.® method, were able to articulate the bigger ideas they’d be trying to come to a consensus on – as one of their members reminded them, so far “[they hadn’t] been able to define what a soul is”; at GPS the students became increasingly confident to challenge one another to excerpt from text. Across the discussions, there was a strong sense of joint endeavor and collegiality within each student group.

3. R.E.A.L.® for inclusion

For me, the power of R.E.A.L.® above all lies in its inclusivity. Done badly, class discussion can often favor more confident students whilst excluding other students from the learning process.

R.E.A.L.® not only gives all students a way in through its shared language and routines, it also shifts students’ understanding of the purpose of discussion so that full participation from the group is seen as a goal.

At all three schools, I observed the most competent speakers taking on the role of facilitator, in which they invited their quieter peers to contribute to the discussion. Rather than the teacher taking charge to ensure equity, there were frequent examples of the students being empowered to question and prompt one another to ensure a balance of voices.

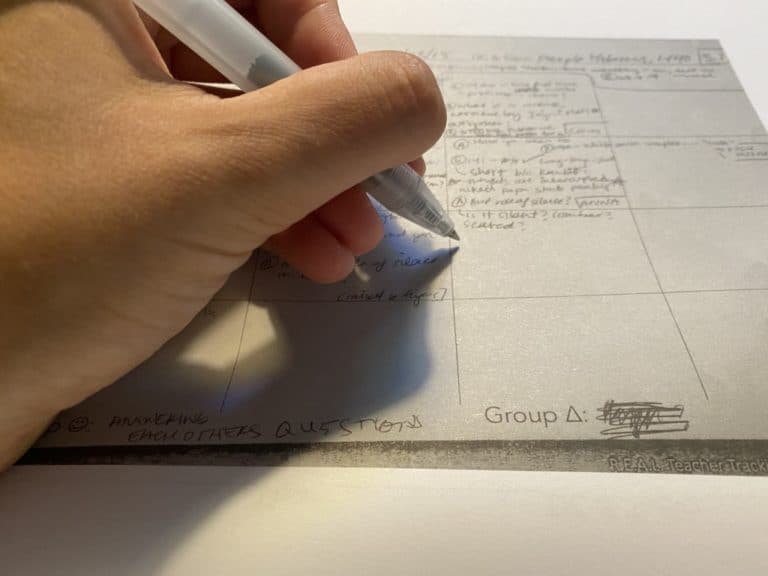

4. R.E.A.L.® for assessment

The R.E.A.L.® approach provides a clear assessment framework of decontextualized skills, which also directly maps to the skills required in English and humanities classrooms. I saw in big and small ways how students were able to access this framework to self-monitor, self-assess and continuously improve their participation. In their individual reflections, students at all three schools considered their performance against the targets they had set themselves and were able to view their progress over time. At Hutchison, students’ reflective responses to classmates’ contributions exemplified Hattie’s view of the importance of dialogue as a tool for revealing students’ learning.

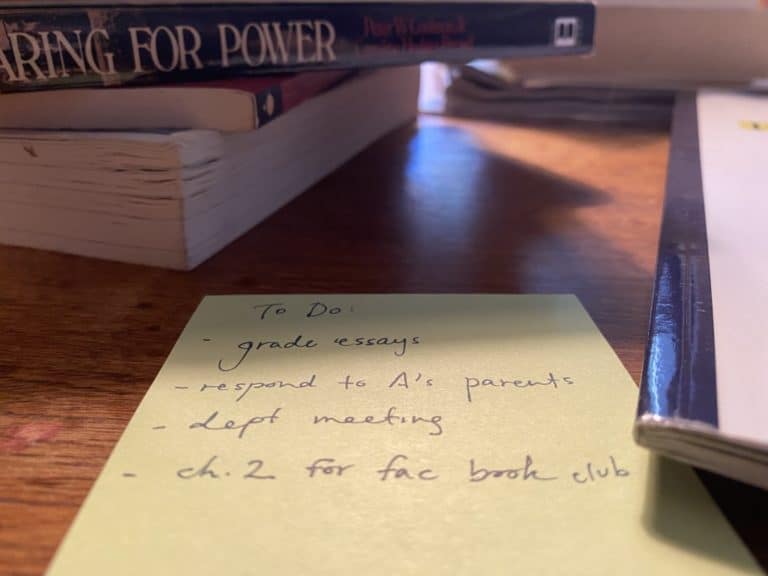

5. R.E.A.L.® for professional development

In my experience, a lack of consistency in teaching approach is one of the biggest barriers to students’ developing their speaking and listening skills. The R.E.A.L.® approach provides teachers as much as their students with a clear roadmap for how to develop a set of effective, generic discussion skills that can be applied across topics and subjects and builds over time. All of the R.E.A.L.® teachers I spoke with talked about the initial investment of time in establishing the routines of discussion and the fluency their students have developed over time.

How can I apply R.E.A.L.® in my classroom?

Although my own school context and curriculum in London differ significantly from the schools I visited in Tennessee, the principles of R.E.A.L.® – namely, rigorous routines, reflection time, participation for all, a robust assessment framework, and a consistent teaching strategy – can be applied to foster effective student discussion in any classroom. My next steps are to grow these strategies within my English faculty through creating discussion-based lessons that use the principles of R.E.A.L.®, training colleagues to facilitate student-led discussion, and working with the humanities team to lead on a consistent whole school approach to speaking and listening.

Above all, I’m convinced through my conversations with teachers and observations of R.E.A.L.® classrooms of the importance of investing time to embed the skills and routines our young people need to develop effective speaking and listening; at each stage and discussion cycle the students I observed in Tennessee were using the R.E.A.L.® framework to become increasingly confident, independent and self-reflective participants in their discussions.